Canmore Alberta - No one could ever accuse writer Stephen R. Bown of lacking ambition in his most

recent books.

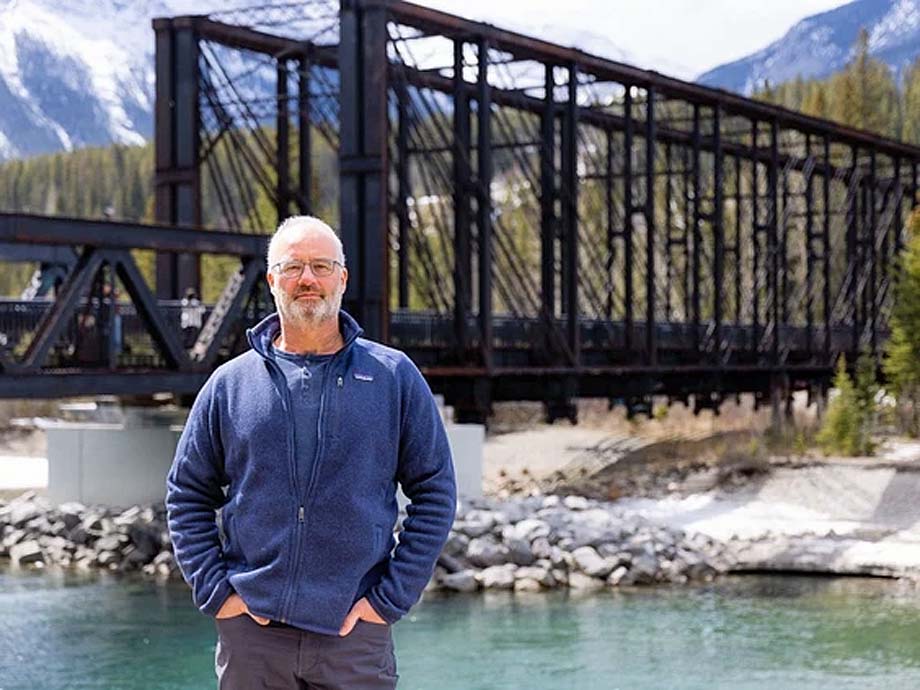

In 2020, the Canmore-based author published "The Company: The Rise and Fall of Hudson's Bay Empire", a

revisionist take on the fur-trading juggernaut and the impact it had on the formation and development of our

country.

Bown, who has written 11 historical books on everything from early 20th-century Arctic explorer Roald Amundsen to the

1741 shipwreck of the St. Peter along the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, suspected that most Canadians only thought they

knew the history of "The Company" and that the real story had never been fully documented.

The 500 page tome won the J.W. Dafoe Book Prize, and the National Business Book Award, and Bown was praised for his

exhaustive research.

When it came to following up that book, Bown zeroed in on another nation-making project, the building of the Canadian

Pacific Railway.

As with Hudson's Bay, the story of the CPR had been told before.

But, as with past takes on Hudson's Bay, Bown saw that past explorations did not do a particularly good job of

documenting the true cost of this wildly ambitious enterprise.

More than 3,000 kilometres of track was constructed, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific to connect the the

British colonies in the late 19th century.

It was a formidable task and helped create modern Canada.

But for Bown, retelling the history wasn't enough.

"What I wanted to do was update the national narrative on some of these big events to show multiple dimensions of

it," says Bown, in an interview from his home in Canmore.

"I won't even say both sides, because clearly there are a whole bunch of different things going on and points of

view. If we can broaden the national story to include all the divergent voices from that time period and different

perspectives of what was going on, and the stories about how some people were thriving, and others were being crushed

down, then at least we'll have some basis in fact for understanding the world and draw people together so at least

there is a common foundation."

In the first paragraph of the introduction to "Dominion: The Railway and the Rise of Canada", Bown makes it

clear that his account will not be a repeat of past chronicles, including Pierre Burton's national cheerleading in

1970's "The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881" and "1971's The Last Spike: The Great Railway,

1881-1885".

Bown acknowledges the Canadian Pacific Railway as Canada's "first and greatest megaproject, a political and

engineering feat of staggering dimension" but writes it also a "horrible environmental and social

tragedy" that "enabled the often-cruel repression of the land's original inhabitants and the exploitation of

thousands of labourers."

Bown says it was the most difficult book he has ever written, joking that maybe he should "go back to writing

about shipwrecks."

But to present different perspectives, he had to find them.

That included consulting resources that wouldn't have been available to writers in the 1970s.

Among the colourful characters Bown introduces in the book is R.M Rylatt, one of the surveyors in British Columbia, who

left England in 1871 to work for the railway, and whose recently unearthed first-hand account of the hardships facing

workers offered a new perspective, and Dukesang Wong, who was among the hundreds of thousands who came to Canada in the

mid-19th century, and through his diary, provided what is believed to be the only first-hand account by a Chinese

railway worker.

"Most of these people were illiterate, so they didn't make any records of their time there," Bown

says.

"They were illiterate in Chinese and English. Dukesang Wong wrote in Chinese, but his journal was very

enlightening. You couldn't include that before because the information doesn't exist, it does now. Also, the journal of

one of the surveyors who was there travelling around, making interesting observations on the world and the changes and

the scenery. That didn't exist either. So it was a combination of new information coming to light and new ways of

looking at it. Rather than just cheerleading about how fast and how speedy the railway came across the prairies, you

might want to look at the number of treaties and how agents were sent out to sign agreements with indigenous people

across the lands specifically to make sure the railway was not going to encounter violent conflict. But, also, John A.

MacDonald wanted to claim all that land as part of Canada although, of course, there were people living on

it."

MacDonald, Canada's first prime minister, was a main player in moving the idea of a railroad ahead, determined to make

Canada a cross-continental country like the United States.

"It was because of his passionate hatred of American expansionism," Bown says.

"He didn't like Americans. He didn't like anything about them. Most of his career was spent trying to prevent

Americans from conquering and taking over all that part of North America. The colony of British Columbia, Victoria on

Vancouver Island, was several thousand people. The gold rush had happened. American miners had swamped in during the

gold rush. Some of them had left. All of their commerce was with California, and San Francisco. To the north of them,

Americans had purchased Alaska. To the south was Washington State, to the east of them were impenetrable mountains, no

roads, no path, no railway, and no way of getting any communication through. It was pretty obvious that whole thing was

going to be part of the U.S. It was only the promise that if you join our new dominion of Canada, we're going to build

you a railroad."

So, in the end, "Dominion" became a book that was not just about the railroad, but a broader look at how the

country was born.

"The whole railway was a massive, dramatic undertaking," he says.

"It was like the spine of the nation. Without the railway, there would be no Canada."

Eric Volmers.

The book is more about the effect politics and the railway had on

the natives rather than a substative history of the Canadian Pacific Railway limited.

The book is more about the effect politics and the railway had on

the natives rather than a substative history of the Canadian Pacific Railway limited.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.