The WP&YR was a narrow gauge railroad extending 110 miles through the coastal mountains from Skagway, Alaska, on the Lynn Canal to Whitehorse, Canada, on the Yukon River.

For the first 20.4 miles the tracks rose 2,865 feet to White Pass Summit with grades up to four percent and 16 degrees of curvature.

On the American side of the border, the roadway was blasted across precipitous rock slopes hundreds of feet above the valley floor.

A 250 foot tunnel cut through a granite ridge, and wooden trestles spanned numerous drainages.

A steel cantilever bridge, that carried the rails 215 feet above Dead Horse Gulch, was the highest in the world when constructed in 1901.

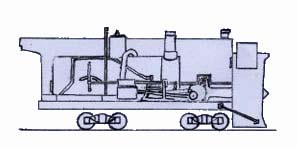

Rotary No. 1 was a coal fired, steam powered, Leslie type snow plow constructed in 1898 by Cooke Locomotive and Machine Works.

It was not self-propelled and was pushed by two steam locomotives.

The lead pusher was locomotive number 70, a 2-8-2 Mikado class built in 1938 by Baldwin Locomotive Works.

The rear pusher was number 72, also a Mikado build by Baldwin in 1947.

Coupled in at the rear was combination car 211 which was used as a tool car.

The baggage section, with cupola, contained re-railing equipment, various spare parts, and tools to repair damaged tracks or snow sheds.

The passenger section accommodated a number of section hands, or additional crew, to remove obstacles or to shovel snow by hand.

Rotary No. 1 contained the firebox, boiler, and horizontal cylinders of a locomotive.

However, all of the steam energy generated was utilized in operating the snow plow system.

The connecting rods of the two horizontal cylinders extended forward of the boiler to drive massive bevel gears that transmitted power to the central shaft of the rotary.

At the front was a hood 11 feet wide and 15 feet high, with a lower lip held three inches above the rails.

The rotary wheel consisted of 10 triangular blades with self-adjusting cutting knives hinged on both edges.

As the wheel rotated at high speed, snow passed through an opening in the upper part of the hood to a fan compartment.

The fan ejected the snow by centrifugal force through an adjustable chute, and cast the snow in a high arch to the side of the track.

The rotary wheel, fan, and chute were reversible in order to throw the snow to either side.

Rotary No. 2, identical to the original one, was purchased from Cooke in 1900 and shared snow clearing duties until Rotary No. 3 was acquired from the Denver & Rio Grande Western railroad in 1943.

Long periods of severe winter storms blanketed the mountains in ever increasing masses of snow.

Raging winds, often accompanied by bitter cold temperatures, swept down the canyons of the Skagway River.

Avalanches, snow slides, rock falls, and icing conditions made keeping the rails open an unpredictable and often difficult and hazardous endeavor.

Ice build-up on the grade, and at switch points, caused by water seepage and small streams, was a serious problem, particularly in spring and fall.

In several areas, ice masses covered the inside rail, and were thick enough to lift the hood and derail the snow plow.

Clearing ice by hand with pick and shovel was an extremely undesirable job that fell to the section hands.

Snow slides and drifts looming above the plow had to be hand shoveled down in steps to the level of the hood.

The clearing was necessary to prevent snow from sloughing against the side of the plow, causing it to become stuck or derailed.

Section hands also had to shovel out rock fragments or boulders that could damage the rotary wheel.

Dressed in bulky winter clothing, they were often buffeted by vicious winds, stinging blasts of snow, and below zero temperatures.

In addition, winter conditions provided only a short period of faint daylight that faded into darkness in the shadow of the towering mountains.

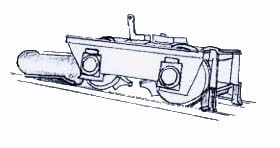

Ice cutters and flangers that could be raised and lowered simultaneously, were mounted on a heavy framework on the front truck of the rotary.

The ice cutters were composed of two parts, a wing that extended down along the inside, or well flange side of the rail, and the cutter blade that skimmed the top of the rail.

They were held in place by shear bolts that allowed the cutters to swing back if the bolts were broken by an obstruction.

The flangers, located just behind the front truck, also were equipped with shear bolts and replaceable cutting edges.

Both flangers were lowered between the rails to remove snow and ice that remained, depositing it in the corner of the cut on each side.

The rotary required a three man crew, engineer, fireman, and the pilot.

The pilot was in command of the entire fleet (the only time a conductor was not in charge).

The pilot operated the plow and controlled the fleet's air brakes from his cab located between the boiler and plow and above the bevel gears.

He signaled instruction to the rotary engineer to adjust the speed of the wheel, using an air whistle.

A steam whistle was used to direct the engineers of the pusher locomotives.

High on the storm-battered peaks, wind whipped cornices grew until overburdened, and great masses of snow and ice broke away.

Falling on the steep upper slopes, it gained almost instantly in size and velocity.

An avalanche formed, a broad river of snow that devoured everything in its path as it became a roaring, churning, stream of destructive force.

Rock and debris, swept up in the descent, scoured a narrowing groove in the side of the mountain before crashing onto the lower slopes in a jumbled pile of compacted snow, ice, and rock.

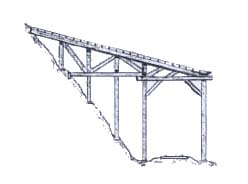

In locations exposed to large avalanches, and in areas of severe drifting, the White Pass built a series of wooden snow sheds.

Six of the sheds were on the American side, and one on the Canadian side.

Two of them were each more than a thousand feet in length.

Where heavy snowfall and deep drifts occurred, some of the sheds were flat topped with braced sides.

However, in avalanche areas, the sheds were designed and constructed to be anchored in the hillside, and to support a sloping roof of large planks that would carry the avalanche over the train passageway to fall harmlessly below.

There were times when a major winter storm held the White Pass immobilized in a freezing grip, day after day.

Hostlers worked through the night to ready the rotary snow fleet for an early call.

The engines and rotary were moved to the coal bunkers to receive a full load of fuel.

Water tanks were filled to capacity, and engine sand domes loaded with dry, screened, sand.

Hostlers then fired up the fleet and moved it to a side track to await the arrival of the train crews.

The sights and sounds that were commonplace when steam engines ruled the rails have receded into the nostalgic haze of history.

Today, few remember waiting at a crossing as a steam locomotive passed, working hard to bring a long train of heavily laden freight cars up to a steady traveling speed.

A towering column of billowing smoke and steam roared from the stack in a hard cacophonous bark of increasing cadence.

The rumbling clatter of steel wheels on steel rails thrummed continuously as the train rolled through the crossing.

Perhaps, the most heartfelt loss, is the deep, tremulous, rise and fall of a steam whistle, fading into the distance on a cold winter night.

Elise Giordano.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

(the image is altered or fake)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.