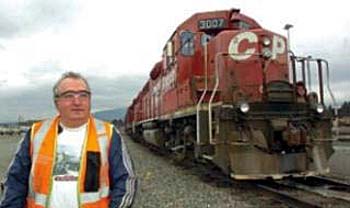

Port Coquitlam British Columbia - Bryan Ness knows his trains.

He has been working around them since he was a teenager, when his job was to light briquettes to keep train loads of perishables warm in winter.

Today, the northside Port Coquitlam dad still works for Canadian Pacific Railway, although now at the PoCo yard, and he's also a history enthusiast, making him the ideal candidate for talking about the company and its involvement in the city's early history.

"I'm not a train man," the burly 53-year-old admits. In fact, he's a crew bus driver, who drives the trainmen around the expansive yard that boarders the West Coast Express station to the west and the Pitt River to the east.

But it's a testament to Ness' interest in trains and PoCo history that he has put together a little slide show that details the rail company's history and how it carved the community out of flat delta land.

In the DVD presentation culled from historical photos and books such as Port Coquitlam, City of Rivers and Mountains, and Port Coquitlam: Where Rails Meet Rivers, Ness describes the political finagling that resulted in a tiny station, Westminster Junction, being built for a spur line to New Westminster in 1886.

Westminster Junction was a modest structure that was built next to the CP line a little west of the PoCo railway bridge. Nothing marks the spot near Kingsway Avenue: there's just some gravel and some brush beside the tracks. The closest building on Kingsway is an orange, triangle-shaped office building that was once Pop's Cafe.

But for many years, it was the centre of town. The station was flanked by no fewer than three hotels, brought trade and commerce to PoCo, and it was where women sent their sons, boyfriends, and husbands off to the First World War.

After the spur line to New Westminster was built, the next major expansion took place when CP amassed more than 600 acres of land for 180 miles of track for marshalling trains, roundhouses, and repair shacks.

The expansion was completed in 1912 and resulted in an explosion of land speculation. Even the local newspaper of the day, the Coquitlam Star, got into the act, bragging the region would become the Pittsburgh of Canada. It published a colour edition of the paper with pictures of steel mills and steam ships, copies of which the Port Coquitlam Heritage and Cultural Society still has in its possession.

There were two reasons for this expansion, notes author Chuck Davis in Port Coquitlam: Where Rails Meet The Rivers: "The railway's 25 year tax exemption in Vancouver was about to expire, and the company believed the opening of the Panama Canal would bring much new business."

In addition to the rail yard, the company built the Pitt River rail bridge, which is still in use today, and the Minnekhada Land Company built the Minnekhada Hotel, later named the Wild Duck Inn, to be a bunk house for CP workers. The inn was torn down recently but a mural dating from the 1950s by an artist who worked at Disney was saved by the heritage society.

For the next 96 years, the rail yard would be a fixture in the city, a boon for those it employed and transported, and a bust for those who wanted to get from one side of the city to another. (The Shaughnessy Street underpass provided some relief when it opened in December 1962 and the planned $132 million Coast Meridian overpass should provide even better access.)

Ness, a PoCo Heritage and Cultural Society member, says the railway can't be undervalued for its importance to transportation in the area.

"That's how people got around in those days. The community really depended on the railway." But it's importance as a commuter rail service clearly waned when the car took over.

The roundhouse was knocked down in 1983 and the Shaughnessy Station shopping mall was built on former CP land. Still, the rail yard employs many people who marshal, repair, and drive freight trains 122 miles to the first stop at North Bend near Boston Bar.

But while the railway may have become less important for passenger rail service, it continues to expand in its role as a major corridor for goods movement. Even now, the company is building an 8,000 foot track expansion to handle growth in container traffic.

Another kind of train, SkyTrain, may even run along its alignment in Port Moody.

Author unknown.

(because there was no image with original article)

*2. Original news article image replaced.

(usually because it's been seen before)

under the provision in Section 29

of the Canadian Copyright

Modernization Act.