Vancouver British Columbia - There was a time in Vancouver's past when the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) as the majority landowner dictated the

growth of the city.

The photo above from the 1920s is a perfect example of how the young city was formed to accommodate the railway.

I can't even imagine a situation like this happening today.

It shows a train crossing busy Hastings Street at Carrall in front of the elegant Merchant Bank building (1913), right through what today is known as Pigeon

Park.

Few people realize that this tiny, triangle-shaped park, sits on the former CPR right-of-way that ran between the Burrard Inlet waterfront and False Creek

Flats.

(The distinctive angles of some of the buildings in the area are lasting evidence of this.)

On 16 July 1932 the mile-long CPR tunnel known as the Dunsmuir Tunnel opened to passenger and freight trains, permanently closing the Carrall Street level

crossing, eliminating the congestion caused by the number of dangerous railway crossings from Vancouver streets.

Shortly after Vancouver's cross-town rail travel went underground, the CPR began tearing up the spur track along the Carrall Street right-of-way from Alexander

Street to the south side of Pender Street in order to prepare the land for sale.

The CPR and the City soon began negotiations for the small triangle of land at Hastings and Carrall Streets.

The relationship between the City of Vancouver and the CPR for this cuneate (wedge shaped) corner began on 14 September 1899 when the City was offered a

small portion of land owned by the CPR at Hastings and Carrall, provided the city would maintain a drinking fountain there.

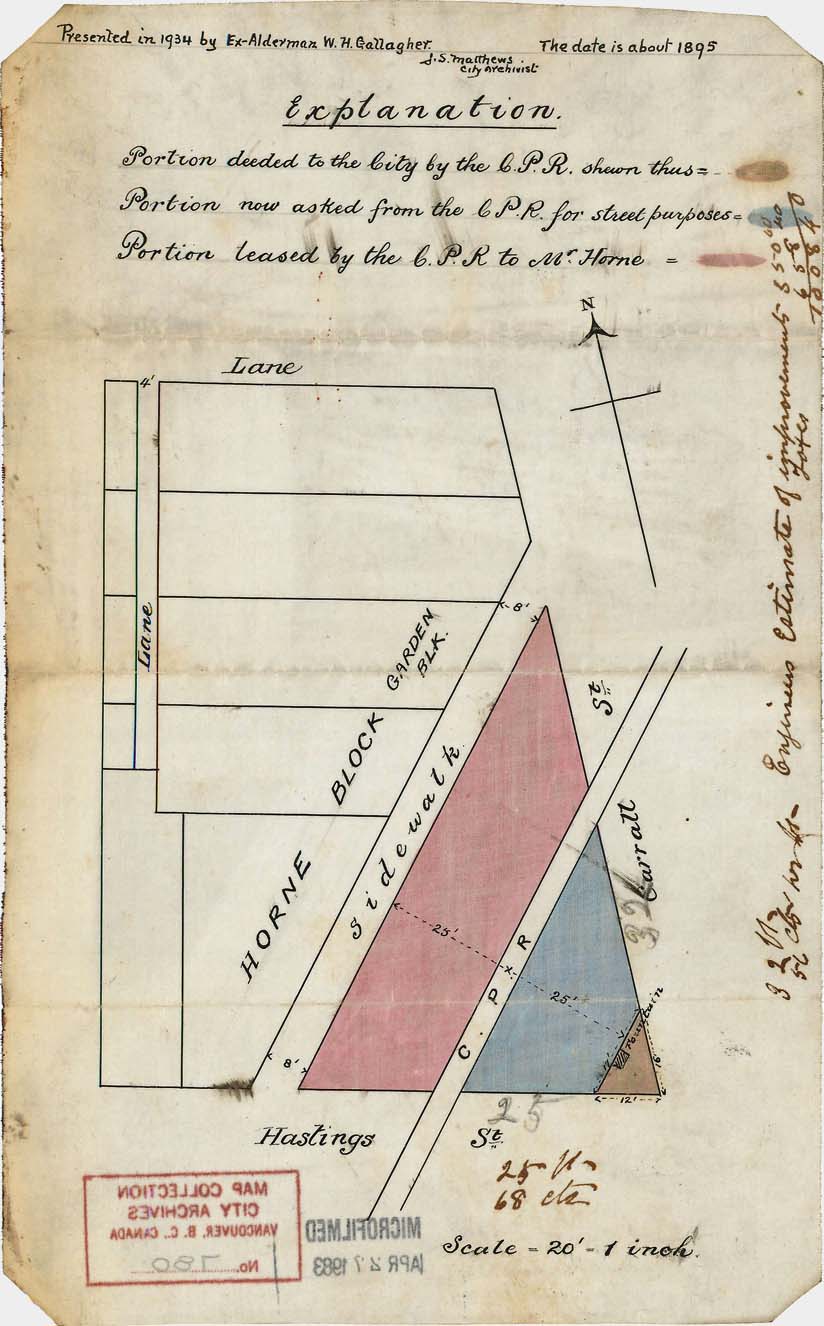

This hand-drawn plan from the City of Vancouver Archives shows the first evidence of the CPR and the City coming into agreement over this portion of

land.

It is colour coded to indicate the portion deeded to the City by the CPR, the portion being asked from the CPR for street purposes, and the portion leased by

the CPR to Mr. J.W. Horne.

An engineer's estimates of improvements are noted on the right side of the map.

This plan also shows the original building that was erected on the lot beside the triangle by real estate developer and Alderman James W. Horne.

At that time, Horne owned more land in the area than any single person, second only to the CPR.

It was replaced by the current building (Merchant's Bank Building) in 1913.

The economic depression of the 1930s hit Vancouver particularly hard.

This area saw many unemployed men and itinerant workers milling around hoping to find work or their next meal.

The photo above from 1935 shows the CPR right-of-way between Cordova and Carrall Streets (north east of Pigeon Park) after the rails were removed.

Places like the old CPR right-of-way were used as ad hoc parks for these men, often to the ire of local businesses.

Shortly after the City officially acquired the land from the CPR for $12,500 in 1937, plans for "beautifying" the former CPR triangle began in

earnest.

The Pioneer's Association wanted some sort of feature, a statue, or small fountain, to adorn the triangle-shaped square.

Local business owners had other ideas.

They hired lawyer Angelo Branca to argue their petition that instead of a "park", the property should be paved and turned into parking

spaces.

They believed that a green space in the area would be a "congregating point for loungers" and be bad for business.

A compromise was reached and a budget of $2,500 was allotted to landscape the area with a patch of grass and flower beds.

The final cost to the city was mitigated by donations of $750 from BC Electric (whose headquarters were across the street from the triangle) and $400 from the

Bank of Montreal.

This park, in the heart of the Hastings Street business and entertainment district, and two blocks from the spot where Vancouver held its first city council

meeting, would officially be named "Pioneer Place".

In the end, the triangular park was simply laid with grass surrounded by a chain link fence.

The 1940s and 1950s saw the beginning of the decline of this once vibrant area of town, and only the men who were debilitated or elderly

remained.

With nowhere to sit, all the men could do is lean on the outside and watch the pigeons feed inside.

Pigeon Park became a place for these men to hang out and drink.

Right from the start, pigeons outnumbered the park's habitues (regulars) and locals started calling it Pigeon Park.

By the late 1960s, this moniker was also being used by the local news media.

Over the years, the constant pecking of the pigeons turned the isolated patch of grass into a sad pit of mud and garbage.

Plans were made to get rid of the grass and pave the area, which would allow city staff to hose the pavement down if the pigeon dirt became

unsightly.

By 1961, on the occasion of the City's 75th anniversary of incorporation, Pioneer Place finally got its commemorative plaque and was fitted out with trees,

benches, and granite stone garden beds.

The City, the locals, and the pigeons were happy.

And then they weren't.

In June 1972, after pressure from local Hastings Street merchants, in a 6-5 vote, city council led by Mayor Tom Campbell under recommendation of the Board of

Administration agreed to the following alterations to the features of Pioneer Place: (1) elimination of all benches, (2) removal of the planter wall thus

leaving a flat surface at sidewalk grade, and (3) lowering and replanting of existing trees, or planter areas at sidewalk elevation.

The move to alter the park and take away the benches came after complaints from area business owners who said, "drunks in the area drove away

customers".

Not only was council split, but also letters to the editor in the Vancouver Sun and to City Council reveal that many citizens disapproved of the decision to

choose profits over people.

During a 1974 Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA) public meeting, Alderman Harry Rankin said that Pigeon Park should have been left the way it was,

"the council said the park was a disgrace. What they were really saying was that the people using it were a disgrace, and that the park should simply be

obliterated to get the people out."

He continued and said, "What we really need in the area is to build a number of parks and provide better conditions so that people do not have to drown

themselves in vanilla extract and rubbing alcohol".

In 1975 the "Golden Pigeon" mural by the Pier Group Mural Company was painted on the exterior wall of 333 Carrall Street at the north edge of Pigeon

Park.

Defiantly watching over the park, it added a much-needed splash of colour in the dull-grey landscape.

Then in 1977, for the fourth time in its 40 years, Pigeon Park was once again "under the knife", and new landscaping and benches were

installed.

This time the City "resuscitated" Pigeon Park using an old-time brick motif like they did for the revitalization of Gastown earlier in the

decade.

Still, the neighbourhood continued to decline.

The 1980s and 1990s brought the introduction of heavy street drugs to the Downtown Eastside.

Provincial government cuts to mental health facilities, social housing, and welfare programs contributed to the downward spiral of this part of the

city.

On 5 November 2016 the Survivors' Totem Pole was raised in Pigeon Park.

An initiative of the Downtown Eastside Sacred Circle Society, and the Vancouver Moving Theatre, it represents a three-year collaboration between First Nations,

Downtown Eastside advocates, the LGBTQ community, Japanese, Chinese, and South Asian survivors of racism.

Haida carver Bernie Williams (Gul Kitt Jaad) led the design and carving of the totem pole, a symbol of healing that celebrates the survivors of the Downtown

Eastside and all those who have survived the effects of colonialism, racism, and poverty.

Today, encroaching gentrification is putting the squeeze on local street residents who have long used Pigeon Park as their "living room", and who

have nowhere else to go.

If not there, then where?

In many ways, the neglect that Pigeon Park has faced over its lifetime reflects those of the Downtown Eastside as a whole.

Christine Hagemoen.