Back

Title

Article

News

Links

In August 1983 the Glenbow-Alberta Institute opened an extensive exhibit commemorating the centennial of the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway at Calgary. This exhibit, which ran until May 1984, effectively combined artifacts, photographs, documents, and paintings pertinent to "The Impact of the Railway on Western Canada, 1883-1930". Construction of the CPR was probably the most significant engineering project in the history of the country. It had profound political, social, and economic influences which, 100 years later, still affect Canadian life. Completion of the CPR was itself a condition of British Columbia's joining the Confederation, and the extension of tracks through the unsettled prairie of what became the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta made possible the settlement of this vast area, with its great potential for agricultural and mineral development. Construction crews, working from the east, reached the foothills of the Rockies at the site of Calgary in 1883, two years before completion of the link with the Pacific.

Like many exhibits, this one at the Glenbow began with more modest aims than the final product suggested. It was originally intended as more of an archival display of some of the Glenbow's excellent photographic and documentary collections, with supplemental material from other sources. As the subject's potential became more evident, however, a larger exhibit developed with more three-dimensional material. Funding, as well as loans of artifacts, came from many sources across Canada, including the CPR itself. In addition, the Glenbow prepared a large-format book and convened a conference to address more closely a variety of themes relating to the CPR and to western Canada1.

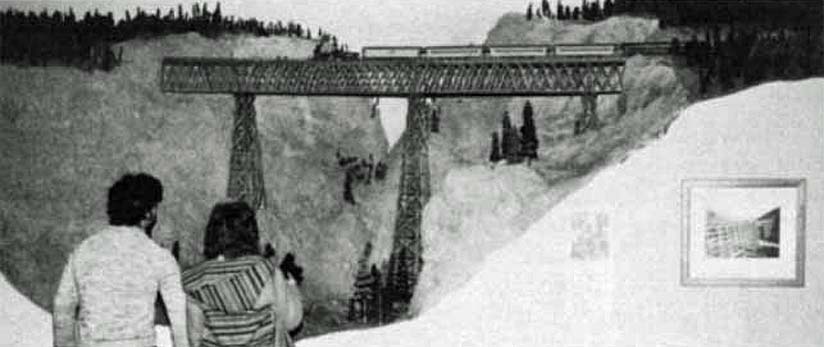

The exhibit had a well conceived story line that basically followed a chronological and topical approach, beginning with the political background of the first Canadian transcontinental and proceeding on into the construction era. The artifacts exhibited included survey documents, plans, construction tools, and personal items belonging to Sir William C. Van Horne, a driving force behind the CPR. Fortunately, construction was thoroughly documented photographically, and extensive use was made of these photos. A large 1:48 diorama depicted tracklaying on the prairies, and construction in the mountains west of Calgary was also well covered. Snow in the Rockies and the Selkirks was such a serious problem that, even though track was completed in November 1885, it could not be opened until the next summer because of the absence of snowsheds. The exhibit included a 1:48 diorama of Stoney Creek Bridge in the Selkirk Range of British Columbia (Fig. 1) and a 3:4 scale reconstruction of a mountain snowshed, the latter somewhat compromised by an operating N scale (1:160) diorama of the Vancouver-Calgary line set into its side. A final segment addressed improvements to the mountain lines, especially the Spiral and Connaught tunnels.

The exhibit then began a broader exploration of the CPR and its effect on the land and its peoples. Of necessity, many aspects of the railway's influence were treated in summary form, yet the visitor came away with an appreciation of just how pervasive that influence has been, and continues to be. There was material on early contact with Native peoples, immigration, settlement, and urbanization. Though politics and labour might have been treated in more depth, these subjects were not ignored. There was a close focus on the coming of the CPR to Calgary, with models, prints, drawings, and another 1:48 diorama, and on the CPR's maritime connections, with fine models of a trans-Pacific liner and of one of the Princess ships that served the intercity trade on the Pacific Coast. One gallery addressed the railway's direct and indirect effect on industries in the West. Overall, while the exhibit presented a justifiably positive view of the CPR, some commentary on the hostility it engendered in various quarters would have provided more balance.

From this point on, the flavor of the presentation changed as it emphasized more life-size exhibits and larger artifacts. A reconstruction of a country railroad station (Fig. 2) was appealing, if somewhat disconcerting in that gaps had been deliberately left in the walls. Close by was a gallery dealing with the CPR's hotels, a section of a 1929 dining car that effectively conveyed a sense of the elegance of first-class travel during the steam era, and two sections of a 1914 sleeper, one showing seating, the other berths made up. The exhibit concluded with a selection of paintings and an acknowledgment panel but no summary statement. A stronger conclusion, even a brief one, could have tied together the many themes that had emerged.

Some aspects of the display and labeling techniques are important to consider. The exhibit text was nicely presented on large copy panels, most of which provided information at two levels, general and detailed, in two typefaces. Some of the longer copy panels were a bit daunting, even for someone deeply interested in the subject, and most visitors probably did not take time to read them in detail. That is unfortunate, because the copy addressed the exhibit's major themes in a clear, intelligent, and pleasing style. There were excerpts from travelers' accounts, quotations from officials such as Van Horne, and reflections on the condition of workers2. The large-format book noted above, intended for a general readership, used a good deal of material from the exhibit and in many ways serves as its permanent record.

Photographs, a major component of the exhibit, were nearly all matted and framed in a traditional gallery presentation (Fig. 3). They required close examination, and small prints sometimes failed to convey a sense of the scale of events, or equipment, or the scope of the topography. While photo murals can be overdone, more of them could have been judiciously used here. Paintings and drawings of the road, its hotels, and the scenery of the West added significant interest, color, and depth.

In general, artifacts and documents were used effectively, though in some situations they could have been better placed in context. As with some of the photos, the mode of display was not always as effective as it might have been. A stained-glass window from the steamer Princess Louise, for example, was hung from the ceiling when it would have been most attractive back lit. Tracklaying tools, on a wall next to one of the dioramas, lacked the impact they could have had if displayed to convey a better understanding of their use. These, however, are minor quibbles. Models were used effectively (the nature of the Glenbow's building precluded any full-size locomotives or rolling stock), and the dioramas built by amateur modellers were well done too. While the impact of the N scale representation of the Vancouver-Calgary line was diminished because of the vast amount of geographical compression required, this was well built, popular with visitors (especially children), and conducive to closer study than the same sort of presentation would have been graphically.

In summary, "The Great CPR Exposition" addressed a worthy topic, was thoroughly enjoyable, educational, and presented visitors with a rare opportunity to view important collections integrated into an intelligent and informative sequence. For such an expansive topic, this was no small accomplishment, and the result was a credit to the Glenbow-Alberta Institute and the staff involved. The Glenbow has now prepared a smaller traveling exhibit for display in other communities in western Canada.

Robert D. Turner - Industrial History Curator with the British Columbia Provincial Museum, Victoria, B.C.