Canadian Prairies - Producer cars were a popular option for farmers in the early days of the grain trade as there were advantages to using

them, the potential ability to access better prices for the producers grain, avoiding elevation charges at the elevator, and accessing the grading and weighing

of grain carried out by Board of Grain Commissioners employees.

There were down sides to using producer cars, however.

A producer had to have sufficient grain of one type and grade to load a car.

While a farmer, in theory, could load different types or grades into a boxcar, this meant "bulkheads" or walls had to be built inside the car to

divide it into different compartments.

As well as the producer bearing the expense of the lumber necessary to do this, the producer had to pay at port for the increased expenses incurred in

unloading such a car.

Railways disliked bulkheading, which appears not to have been a common practice, as it resulted in damage to the wooden sides of the car.

Other down sides to using producer cars included complicated damage claims in the case of producer cars leaking grain and potential demurrage charges in case

loading of the car was slow or there were problems unloading the car at port.

The advantages of a producer car included access to better prices for grain.

In the 1930s, a producer had a number of ways to sell grain.

Pre-1935, a producer had the option of selling wheat through the voluntary pool schemes offered by three pooling organizations operating in each of the Prairie

provinces.

After 1935, a producer had the option of selling wheat through the voluntary pooling scheme operated by the Canadian Wheat Board.

The producer also had the option of marketing grain to private industry, grain companies, grain dealers, or grain brokers.

The farmer could simply take his grain to an elevator and sell it to the grain company operating the elevator.

The grain companies offered what was termed "street" price for grain purchased on the elevator driveway.

The farmer could also market grain to private industry using a producer car.

If the producer had enough grain to load a boxcar, the producer could order a producer car and load it to open a variety of price options.

Once the car was loaded and ready to ship to a port terminal, grain companies or grain dealers could offer to pay "track" price for the grain before

the car even left the point it was loaded at.

Track price was usually higher than street price as the grain companies or dealers knew the grain was loaded on a car and ready to move to port or wherever the

customer wanted it.

Grain cars moving to port were sampled at Winnipeg, Calgary, and Edmonton and the samples graded while the car moved to port.

As a producer car passed these points and was sampled and graded, grain companies or grain dealers could offer the producer a "billed and inspected"

price.

The billed and inspected price was higher than track price as the grade and volume of grain was known.

Plus, the grain was closer to port than where it originated.

When the grain was unloaded and weighed into storage in a port terminal, the producer could then be offered a "spot" price.

Spot price was higher than the billed and inspected price as the grain was at port ready to be loaded onto a vessel.

Usually the "street" price for grain was the lowest available price option, making loading a producer car attractive to a producer.

The Canada Grain Act at this time made reference to special binning.

If an elevator offered special binning, a producer with a car lot of grain could request it for his grain and have his grain kept separate from other grain in

the elevator.

The producer could then load a car through the elevator and still retain ownership of the grain.

Elevation and storage charges would be assessed by the elevator, but loading the car was much easier.

As well as perhaps receiving a higher price for the grain, the producer would avoid elevation charges at the elevator if the producer loaded a producer

car.

In addition, the Board of Grain Commissioners inspectors would inspect, grade, and weigh the grain.

Most producers considered inspectors neutral in their decisions as they did not work for a grain company and would grade and weigh grain more

accurately.

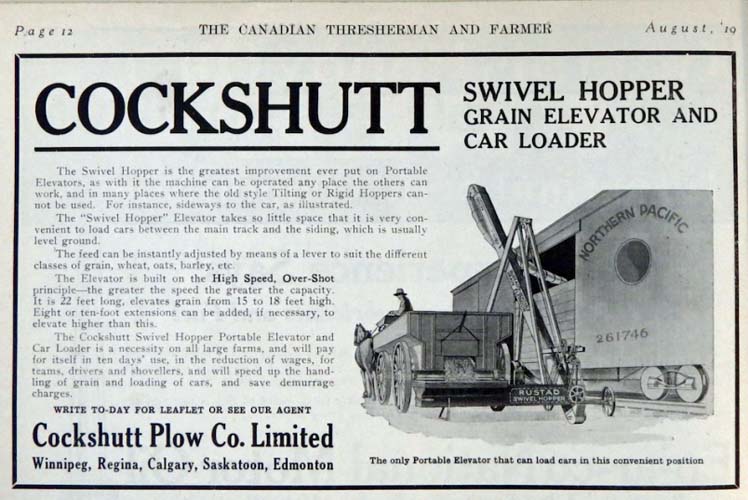

Against these benefits, the producer would have to consider the problems in loading a railcar at the time.

Did the producer have enough grain to fill the car?

Depending on the car supplied, the producer would need approximately 1,800 bushels.

This was an issue particular to harvesting with a threshing machine, which was a slow process making the harvest even more exposed to weather

issues.

Hauling the grain from the farm to load a car was slow and laborious job in the days of grain wagons.

The railways during the fall "grain rush" only allowed 24 hours for loading and would charge demurrage on the car if the car was not loaded 24 hours

after being spotted.

Considering the average grain wagon could haul at most 100 bushels, seven or eight trips would be needed.

A horse drawn wagon was not a particularly speedy vehicle, so a producer working by himself would have to be located within several miles of the rail siding on

which the car was spotted.

In addition, the producer would not be entirely sure when the railcar would arrive for loading.

One thing the producer could count on was that the car would not be arriving on a bright sunny day when the producer had nothing to do.

Author unknown.

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.