Western Canada - Recent articles by the Manitoba Agricultural Museum on loading producer cars mentioned the "no mixing" rule that

was in force in the early days of the western Canadian grain trade.

One reader has inquired about the origin of this rule, which is a very interesting tale.

The "no mixing" rule meant when grain was graded it was to be stored in bins with only grain of that grade.

No other grades of that grain were allowed to be mixed into these bins.

This rule was not imposed upon the industry by some far-off bureaucrat in Ottawa but rather it was agreed to by the entire western Canadian grain industry

including the farmers and came about for two reasons.

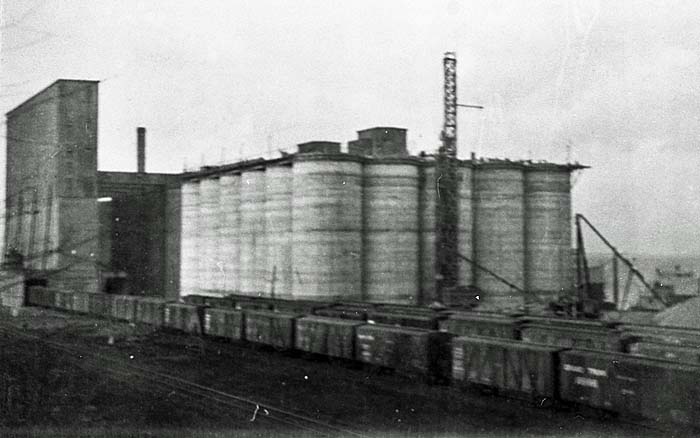

Grain was traditionally shipped by boxcar prior to the adoption of today's center-flow hopper

cars. Today's running trades employees still call a solid train of grain hoppers a "box train" so this is probably

where today's name originated. The Fowler outside braced boxcar was a typical car used during the period of this story.

|

In the very early days of the western Canadian grain trade, the terminals at the lakehead were public terminals and not owned by grain companies.

Public terminals were forbidden to own or market grain.

Public terminals were responsible for the safe return of grain to the owners of the grain stored in the terminals.

While the terminals could have stored separately the various parcels of grain placed into their charge, practical considerations ruled against

this.

Keeping separate the various parcels of grain, all of various tonnages, and all with different and perhaps unknown shipping dates, would have resulted in an

expensive terminal system that was not fluid.

The cheapness and convenience of storing grain in bulk led to the idea that any entity storing grain in a public terminal would receive back grain of the

identical grade but not necessarily the same grain delivered by the entity.

In other words, if an entity delivered into a public terminal, Manitoba Northern Number 1 wheat, the public terminal would store this wheat in a bin that may

contain wheat from another entity which was also grading Manitoba Northern Number 1.

The companies and individuals which delivered grain into the public terminal, marketed this grain, and when a customer for the grain was found by a company or

individual, this entity ordered the public terminal to load a vessel to deliver the grain.

While it may or may not be the exact grain the entity had delivered, it was the tonnage the entity had delivered and of the same grade, so minimizing

disputes.

This method of operation also resulted in fluid port terminal operations.

The system further evolved so that when an owner of grain at a port public terminal requested a vessel to be loaded, the vessel was directed to the public

terminal at this port with an adequate stock of the grade of grain needed and that was best able to load the vessel regardless of which port terminal had

stored the owner's grain and had issued a port terminal receipt when the grain was unloaded.

Once the vessel was loaded, inspected, and on its way, the port terminal receipts for grain issued to the various owners of the grain involved would be swapped

around to regularize the situation.

Fluidity of port operations was further enhanced with this method.

While fluidity of port terminal operations was important, a more important reason for the emergence of the "no mixing" rule was the belief that the

interests of the western Canadian grain growers, and of the Canadian grain trade, would be best served by marketing properly cleaned grain of the "average

standard of the grade."

The average standard of the grade required a no mixing rule to to be in place.

The "average standard of the grade" is not a term familiar to the modern grain trade and so requires some explanation.

While grain inspectors may grade a boxcar of grain as a particular grade, this carload may show considerable variation in quality as compared to other carloads

which also fell into that grade.

Some carloads would have just crept into the grade while yet other carloads of the same grade would have just missed getting into the next-highest

grade.

But the various carloads of the same grade would be dumped into bins in public terminals with no other grades allowed to be mixed in.

Rail cars would be coming into the port terminals from all over Manitoba and the Northwest Territories and from grain companies and grain dealers as well as

producer cars.

So grain in a bin came from a variety of sources spread across the Prairies and could then be seen as being the "average standard of the grade" which

then resulted in the grain being of higher quality than the minimum of the grade as defined by the Grain Act of that time.

The average standard of the grade emphasized to the grain growers the importance of producing grain of high quality by assuring them the reputation of

Canadian grain to customers rested in the hands of the industry which included grain producers.

The no mixing rule and the idea of average standard of the grade enjoyed support from the majority of western producers.

As well, other segments of the industry supported these ideas.

William Van Horne, general manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP), wrote in 1892 that he held the manipulation (mixing) of grain at terminal or transfer

stations to be wrong.

He thought the practice of mixing in many of the private elevators in the U.S. was a source of scandal.

Van Horne also publicly stated that the only western Canadian grain that customers were interested in obtaining were the higher grades.

Lower grades of grain were available to the customers from other sources which were closer to the customer and which resulted in lower transport charges to the

customer.

The Winnipeg Grain and Produce Exchange in 1899 passed the resolution, "The exchange expresses its positive conviction that no mixing of grain should be

permitted at terminal elevators and also no mixing should be permitted in a cargo shipment unless the inspection certificate issued therefore shall have

written across the face, a statement defining the various grades entering into the composition."

While the no mixing rule enjoyed support from the industry there were pressures on the rule.

A significant issue with the rule was the problem of tough grain as well as grain affected with smut, rust, and other diseases.

Under the rules in place, rail cars containing grain with these problems were graded at Winnipeg on their way to port.

Once the grade was assigned it was not allowed to be graded at a higher grade, even when the grain had been dried or otherwise treated to address the

problem.

The volume of tough grain and grains with other issues was such that the first "hospital" elevator came into existence in 1905 and others soon

followed.

Hospital elevators cleaned, scoured, treated with lime or sulphur, washed or dried grain, and in doing so improved the grading characteristics.

With the no mixing rule in place "improved" grain coming out of a hospital elevator was not eligible to be placed in a cargo unless the inspection

certificate for the cargo noted this grain.

Few customers were eager to accept such cargoes unless it was discounted in price.

This, in turn, meant farmers with such grain were offered correspondingly lower prices.

In addition this, grain had to be kept separate in the handling system which negatively affected the fluidity of the system.

To complicate the no mixing rule issue, private port terminals could do whatever they wanted with their property and were only allowed to handle their own

grain so the no mixing rule was not applicable to them.

Between 1912 and 1929 there were a number of revisions to the Canada Grain Act of 1912.

These revisions produced some ambiguity to the rules which allowed hospital elevators to legally mix grain.

This resulted in private and several public port terminals changing their classification to hospital elevators.

A further revision to the Grain Act saw the hospital elevators change to being classed as semi-public terminals as again this type of terminal could mix

grain.

However, in 1929 after discontent by farmers the act was revised again with the no mixing rule affirmed but only for the top grades of wheat.

With the emergence of the Canadian Wheat Board in 1935, farmer support for the no mixing rule weakened, and by the 1950s the rule was no longer in

force.

While it can be debated as to whether the no mixing rule was wise policy, the rule appears to have contributed significantly to the reputation that western

Canadian grain, particularly wheat, built with customers in the early days of the western Canadian grain trade.

This reputation remains useful in marketing.

In the early 2000s the Canadian Wheat Board found that it was a useful marketing strategy to bring up the old grade name "Manitoba Northern" as this

name was remembered by the wheat millers and bakers of the world as representing a high-quality wheat that never let them down.

Since the demise of the Canadian Wheat Board, the industry has been reminded of the need for quality as witnessed by the reclassification of various wheat

varieties allowed into production plus current experiences in marketing grains.

Author unknown.

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.