Canada - The driving of the Last Spike may have been the great symbolic act of Canada's first century, but it was actually a gloomy

spectacle.

The cash starved Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) couldn't afford a splashy celebration, and so only a handful of dignitaries and company men convened on the

dull, grey, morning of 7 Nov 1885 to celebrate the completion of the transcontinental railway.

Major A.B. Rogers held a tie bar under the final rail, set at Craigellachie in Eagle Pass, British Columbia, where construction teams from the west and east

converged.

The honour of driving the ceremonial Last Spike was assigned to Donald Smith, the eldest of the four directors of the CP present.

His first swing of the hammer was off, bending the spike so badly that it had to be replaced.

He posed again with hammer in hand.

The camera clicked, and clicked again, as he landed a successful blow.

The resulting photographs are among the most iconic in Canadian history.

But the images are perhaps more remarkable for the faces they don't show, proving that while an image can speak so many words, it can also gloss over

volumes.

What of the men who actually built the railway?

Where are their names recorded?

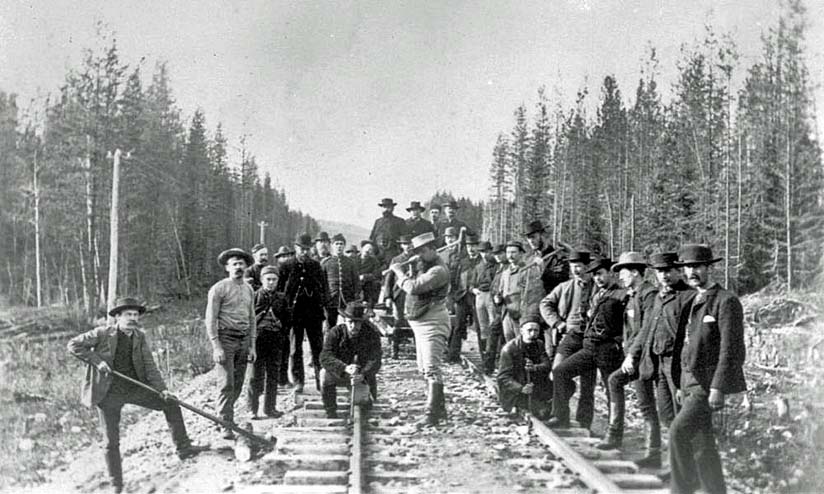

On that same November day, workers waiting for the train to take them east stood for a photo near Donald, British Columbia, some 170 kilometres out from

Craigellachie.

The photos they took seem to be their own version of the iconic photo of the Last Spike.

One man stands at centre, with sledge raised confidently above his head, his grip and stance more certain than Smith's timid and hunched pose.

Though the photos cannot tell us whether these workers knew of the image taken that same day, of men in suits and ties, they tell us in part, who really built

the railway to the Pacific.

In his book, The Last Spike, historian Pierre Berton follows Charles Alfred Peyton as he looks for work along a stretch of track construction on the

Prairies.

Along the way, Peyton encounters a band of Italians at one spot, and a group of Englishmen at another.

But Berton also walks the reader past a scholar who can speak and write Greek, a surgeon from Montreal, and a pastor from Chicago.

The railway labourers, it becomes clear, were a mixed group.

Generally, though, Berton describes the men as a rough-and-tumble lot with ill manners and disagreeable mouths.

They were there for the $2.00 to $2.50 a day, which was good pay for the time.

Work on the Prairie section might have seemed like chaos to Peyton, who describes a fellow labourer firing shots at him over a bundle of

firewood.

(Gunplay, it seems, was not uncommon in the work camps.)

But the actual construction was organized down to the last detail.

"The track layers worked like a drill team," writes Berton.

The ties were unloaded, and then hauled by mule teams, and set into place by hand.

"Right behind the teams came a hand-truck hauled by two horses, and loaded with rails, fishplates, and spikes."

In a steady rhythm, men tossed the rails into position, and hammered them down with spikes.

Conditions were harder for the men north of Lake Superior, where blasting through the Canadian Shield came at great cost in human lives.

But the most extreme working conditions were in the mountain ranges of British Columbia, where thousands of Chinese labourers toiled.

Men were routinely mangled or killed by falling rocks, by landslides, by avalanches, and above all, by incessant nitro blasts that hurtled rocks out of tunnels

like cannon balls.

Death was far more frequent among the Chinese than other groups, and historians estimate that at least 600 died.

Some estimates are in the thousands.

Andrew Onderdonk, the contractor in charge of construction between Port Moody and Kamloops Lake, estimated that he would need at least 10,000 men to build his

section of the railway.

His solution of bringing workers from China horrified the racist population of British Columbia.

The BC government tried to ban the Chinese, but in 1882 Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald said plainly in the House of Commons, "either you must have

this labour or you can't have the railway."

Onderdonk paid the Chinese less, only one dollar a day, forced them to buy all of their supplies from the company store, and made them build their own

camps.

All this they agreed to do, for the money they saved would serve them for life in China.

Or so they were led to believe.

Instead, after living and work expenses, most Chinese workers were unable to save enough money to even pay down debts for their ticket to Canada.

To add insult to injury, the prohibitive Chinese head tax was set in place just months after the Last Spike was driven.

A measure to dissuade Chinese immigration, the tax for entry to Canada was set slightly higher than the average amount of money a Chinese worker could save in

one year.

Though there are no Chinese labourers in either image of the Last Spike, their contributions to a developing country speak more than a thousand

words.

James H. Marsh and Eli Yarhi.

There's also a silver spike, a spike knife, and much more to the mystery

There's also a silver spike, a spike knife, and much more to the mystery here.

here.

(because there was no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.