Canada - Railway dicks know how to handle gunmen, swindlers, and passengers who lose their bags.

But small boys!

There is something about railways that seems to invite crime.

As one railway policeman put it, "People who wouldn't steal anywhere else steal from the railways."

They steal everything from washroom towels to locomotives.

As a matter of actual fact a full-sized locomotive was taken right out from under the noses of a train crew in Winnipeg a couple of years ago.

It was locomotive 5090.

She was standing at the Fort Rouge roundhouse with steam up just waiting for her crew to hiich her to a passenger train for Shilo, Manitoba.

As a trainman watched, amazed, the supposedly unoccupied engine started, picked up speed, and slammed into a baggage car, causing considerable

damage.

The runaway locomotive stopped and began to back away from the wreck.

An engineer tried to climb into the cab to stop it, only to be kicked in the chest and sent sprawling.

The engine headed back toward the Fort Rouge roundhouse picking up speed as she went.

To avert a crash, a switchman threw her onto the main line.

Two miles up the track 5090 stopped, out of steam, and a young man jumped from the cab and vanished into the nearby bushes.

That's where the railway police stepped in.

The Canadian National Railway (CN) investigators didn't have much to go on as the stunned witnesses had only a fleeting glimpse of the thief.

The sleuths traced down a hundred false leads, and then, on a tip from an alert call boy, they nabbed a 16-year-old engine-crazy youth in the act of preparing

to steal another locomotive.

He was prosecuted by the Winnipeg juvenile courts.

Canada's 1,000 odd railway policemen don't chase locomotive thieves every day, but they do have more excitement than you'd guess when you see them standing

around larger railway depots keeping people from going where they shouldn't, answering questions, and generally making themselves useful.

They protect paasengers from each other and themselves, escort valuable shipments of gold, silks, or furs, and keep the wrong people off railway

property.

They also trace down articles lost or stolen on railway property, and that sometimes brings them up against tough criminals and gunmen with whom they have to

shoot it out.

Statistics tell just how big a job railway police do.

During 1946 the CN cops made 2,096 arrests in Canada and the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) force made 1,990.

And railway police don't arrest just anybody who looks suspicious.

They are private police and have to be sure of their ground before laying a charge.

So sure in fact that they get convictions in over 98 percent of cases.

Like most policemen the railway cop spends most of his time on dull routine investigation.

But he runs into melodrama too.

For instance there was the gun battle that took place a few years ago at the town of Lanoraie, 50 miles east of Montreal.

Cigarettes were disappearing from freight cars in the yards there, and the CP police set a trap to catch the thieves red-handed.

Every night a couple of plain-clothes investigators would get on a passenger train in Montreal and ride out to Lanoraie.

Before the train stopped they would jump off the side away from the station platform and slip into the bushes from where they could watch the freight

cars.

For two weeks nothing happened.

Then, one night investigators George Miller and William Mackie were crouched down in the bushes waiting and watching as usual.

At 02:00 Miller touched Mackie lightly on the shoulder and pointed to a car on the siding.

"There's the boys we're looking for," he whispered.

Mackie saw two dark forms furtively working at the car door seal.

The two policemen waited tensely.

The thieves finally broke the seal and started to open the door.

"Okay. This is where we move in," breathed Mackie.

They rushed the car.

One of the crooks ran down the track and disappeared into the darkness.

The other ducked under the freight car and without warning opened fire with a 38.

Mackie and Miller kept on coming.

Four of the slugs caught investigator Mackie in the chest and arms.

But he kept on coming and with Miller capturing the gunman.

Mackie was immediately rushed to hospital but died of his wounds before morning.

The gunman turned out to be a desperate character with a long police record.

He was taken to Montreal, carefully searched, and clamped into a jail cell.

In the middle of the night the guard found him in the last spasms of strychnine poisoning.

He had carried a small vial of poison in a hole under one of his rubber heels.

The thug who beat it down the track was captured the same night by the combined efforts of CP and local police.

He got 14 years for manslaughter.

"You never know on a case like that," said Inspector Jean Belanger of the CP's Quebec district, who told me the story.

"It might be a couple of kids looking for a smoke, or it might be desperate criminals who will shoot as soon as they see you."

One reason railways need their own cops is that many areas where their lines run are inadequately policed.

Before the CP force was organized by Lord Shaughnessy in 1912 the company was losing millions of dollars annually to thieves and vandals.

Freight cars that had been fully loaded would arrive at their destinations empty.

Now the CP has 432 policemen all told, stationed in every part of the system.

The present CN force was organized in 1922 at the time of the amalgamation of the old Canadian Government Railways, the Grand Trunk, and the Canadian Northern,

which all had more-or-less adequate police forces of their own.

The CN has about 600 police in Canada, and more on its lines in the United States.

The Sabotage Case

During the war the police departments of both railways took every precaution against sabotage, they increased their staffs with special watchmen, and

investigated every employee from the presidents down.

The biggest case they had to handle happened on the night of 15 Jun 1940 at the extremely important tunnel that runs under the St. Clair River between Port

Huron, Michigan, and Sarnia, Ontario.

Constable Laing who was escorting a freight train from the American side through the tunnel, saw smoke pouring out of one of the box cars.

He stopped the train, broke the seal on the door and discovered the whole interior of the car in flames.

Since this car contained valuable, but non-inflammable airplane engines, the police at once suspected enemy sabotage.

Every available police force of two countries, the FBI, the RCMP, the CN investigation department, the Michigan State Police, the sheriff's office at Port

Huron, and the Sarnia police, jumped into action.

But no dastardly saboteur was turned up.

And finally, one of the employees who had "worked" the car in Port Huron broke down and confessed.

He'd been sneaking a smoke, heard someone coming, and had shaken his pipe out on the floor.

The draught created by the moving train fanned these sparks into a first-class fire.

Officials of both railways are pretty proud that that was their biggest sabotage case.

In some respects railway police have more authority than city or provincial police.

A railway constable sworn in before a magistrate has authority anywhere in Canada.

His beat is, of course, railway property, which includes one quarter mile on either side of the tracks.

But in case of a "fresh pursuit" of a crime committed on railway property he may go anywhere.

CP investigators and CN special agents are often sworn in as special constables of the RCMP, this gives them authority anywhere in the province in which they

are stationed.

In the city of Montreal, for instance, the CP maintains three cars equipped with two-way radio sets which patrol the streets at all times, principally to

investigate thefts from the company's delivery trucks.

Recently one of these cars pulled into a yard just as a load of stolen express was being delivered to a notorious Montreal "fence" and caught the

thieves and the receiver of stolen goods red-handed.

Another time they tracked down and arrested an enterprising youth who had got hold of an expressman's cap, waybill book, and other equipment.

He was doing up parcels of rubbish all nice and regular, delivering them to houses, and collecting express charges.

Railway police usually work hand in glove with federal, provincial, and municipal forces, and stay in the background when credit is being handed out for smart

police work.

Cashing in on Wits

A good example of this co-operation is found in the laying by the heels of a couple of ultra slick forgers who were swindling sums of money from railway

stations and hotels a few years back.

The front man of this team was a good-looking, well-dressed, personable smoothy by the name of M. James McKeen.

He would breeze into a hotel carrying expensive luggage, register in one of his many aliases, and ask for his mail.

There was always a letter waiting for him and it was always from his "firm."

It was always on expensive letterhead sationary, and strangely enough, it always contained a cheque for some plausible amount like $116.29.

"Ah, my expense account for the last week," McKeen would announce, and hand it to the clerk for cashing.

Since the cheque had been made out on a checkograph, and since it was certified by a bank the clerk wouldn't hesitate a minute.

Sometime later that day McKeen would get a wire from his "firm" instructing him to move on, but fast.

It would be some time before the hotel would discover that their gold seal cheque was as rubber as McKeen's heels.

CN Special Agent Menard and CP Investigator Bissonnette worked on this one.

They visited the hotels McKeen had swindled and got his description, a list of his aliases, samples of his handwriting, and anything else about him they could

pick up.

Then they circulated this information to hotels and local police forces in all areas where McKeen might be expected to go.

McKeen was finally caught in the middle of his little act in the Chateau Champlain in Quebec City, but not before he had passed over $800 worth of phony

cheques.

They got McKeen's accomplice, too, a character named Wilfred Haines who was the brains of the organization, and a slick man with a pen.

Haines operated from a small room in Montreal where he had surrounded himself with some interesting equipment including a checkograph, rubber stamps of various

banks, and a small press for printing phony letterheads.

McKeen got three years for forgery, Haines got five, and the Quebec city police got the credit for the pinch.

The expert con men and card sharpers who used to work the trains have pretty well had their day.

However, there are still a few gullible souls losing their money to smooth operators.

George A. Shea, director of investigation for the CN, gave me a just about perfect example of how easily this can happen.

The scene was a day coach of a CN train in Bonaventure Station in Montreal.

A clergyman waiting for the train to start noticed a couple of clean-cut youths across the aisle trying to stuff a large wad of one dollar bills into an

envelope.

He watched them for a while with growing concern and then leaned over and said, "Boys, I hope you're not planning to mail that!"

One of the boys turned his frank open countenance to the clergyman and said, "Yes, sir, you see it's the only way we have of sending this $50 to

Mother."

The clergyman was a dead duck from there on in.

He explained to the boys that they were taking a terrible risk sending money that way.

They said they knew it, but didn't have time to get off the train and buy a money order.

Well, it just happened that the clergyman had two 20's and a 10 which he gave them and which they quickly stuck in another envelope and sealed.

But when they counted the one dollar bills for some reason there were only 49 of them.

The boys frantically searched their pockets but couldn't find another dollar.

Finally they thought of a friend in the next car who could lend them a buck and so they dashed off to see him, leaving the clergyman with the envelope they'd

been stuffing with one dollar bills.

The boys never came back, and when the clergyman was finally persuaded by the conductor to open the envelope he was holding for the boys he found it full

of... toilet paper!

The boys were never caught.

According to Director Shea, there is very little that a policeman can do to protect, big-hearted, but gullible people like that, on a train or anywhere

else.

The Wandering Baggage

Tracing lost or stolen personal baggage and parcels is a big part of the railway dick's chores.

In 1946 the CP force recovered $35,675 worth of such articles for its passengers.

For instance, there was the Toronto lady who got off a CP train one prewar morning in Montreal and discovered she was short four pieces of

luggage.

Railway sleuths immediately took up the trail.

After questioning over half a hundred redcaps, they found one who remembered loading just such luggage on the parlor car of the Empress Special.

The sleuth wired Quebec only to find that the bags had been loaded aboard an ocean liner on its way to France.

A radio message was sent to the liner which was then between Southampton and Cherbourg.

Sure enough, the four wandering pieces were aboard.

They were shipped back by the next boat.

Bags get mixed up every day.

A Saint John, New Brunswick, man arrived at his Montreal hotel, unlocked his bag with the same key he'd locked it with, reached for a fresh shirt and found

instead nothing but babies' didies and other whatnots.

The police searched the bag thoroughly and discovered that it belonged to a Saint John lady who had gone on to Hamilton and was having some trouble dressing

her two-month-old baby in jockey shorts.

The two bags were identical in every way.

Occasionally the police do have to cope with some pretty cagey and ingenious Pullman car thieves.

There was the slight, wiry 17-year-old lad who operated in that long, dreary, stretch of road between Ottawa and Winnipeg.

He would get on at some small station late at night, and while the porter was busy in the washrooms, would lift wallets from trouser pockets, and pick up any

likely looking baggage that was handy.

But a trainman saw him on the train more than once, got suspicious, and the police were waiting for him at his next stop.

They had no trouble spotting him since the expensive luggage and the shabby youth just didn't match.

Railway police rarely ride trains, they prefer to hide at the scene of the crime and wait for the thieves to show up.

During the war travelling servicemen were a bit of a problem at times on passenger trains, but the Army, Navy, and Air Force kept the trains pretty well

policed by their own provost corps.

Sometimes on certain runs, such as up to lumber camps, or big construction jobs, a constable or plain-clothes man will go along to keep the boys in

line.

But only 104 of the CP's 1,990 arrests last year were for drunkenness.

Enemy Number One

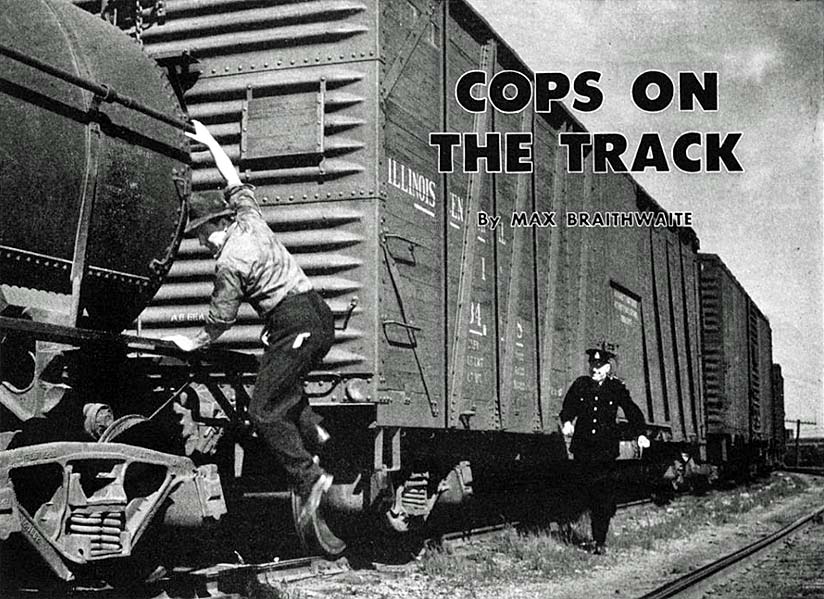

Most people think of the railway cop's job as chiefly a matter of pinching rod-riders.

Last year the CP police arrested 654 ride stealers and kicked off, or prevented from boarding, 2,835 nonpaying customers.

Incidentally, the report states also that altogether 4,043 were observed riding the "sidedoor pullmans," which is more than double the 1945

figure.

In the West, particularly, ride stealing transients create a lot of headaches for railway cops.

They break into freight cars and vans, threaten and intimidate railway employees, light fires in empty cars, damage stations and water tanks, and generally

create accident hazards.

It's dangerous, too.

During the past year 13 illegal riders were killed and 20 injured on the western lines of the CP alone.

"Most people think that we are pretty mean for kicking transients off the trains," Inspector Belanger said, "but it is surprising how many

hoboes are lawbreakers in other ways."

In proof of this he cites the case of Investigator A. Dore who was checking up on bums riding between Three Rivers and Montreal.

Dore grabbed a pair with unusually large packs, which turned out to be stuffed with expensive ladies' wear.

The men were wanted at Three Rivers for breaking into a store near the station.

"They got two years," said Belanger, with some satisfaction.

Both CN and CP investigation officers stated emphatically that the thing that gave them the biggest headaches was not holdup men, or bandits, or bums, or

pullman thieves, but kids, dear, sweet, innocent, little boys.

They steal rides on freights and get themselves run over, throw stones through passenger car windows, break insulators with their slingshots, put obstructions

on the tracks, and indulge in many other childish pranks that cost the railway thousands of dollars a year and often cause actual loss of life.

For instance, a signal maintenance man was rattling along at about 30 miles an hour on his jigger when it suddenly jumped the track and threw him about 40

feet, killing him instantly.

He left a wife and four children.

Some kid had put a spike on the track just to have it flattened out!

And just this last May, an 11-year-old boy returning from church along the railway track to his home in St. Jean Chrysostome, Quebec, happened to find a nut

from a bolt.

Just for the fun of it, he put it on the rail.

The next freight that came along jumped the track.

The engineer, fireman, and brakeman were all injured and 11 horses were killed.

The CN police caught up with the lad and he was given two years suspended sentence on his father's bond of $500.

So serious has the kid menace become that the railways have instituted a special educational campaign.

They send speakers around to the schools to warn the children of the dangers of playing on the tracks and of throwing things at trains.

Director Shea isn't too sure how this will work out.

"Sometimes I wonder if we don't just put the idea of playing on the tracks into their heads," he says.

Crooks on the High Seas

One of the biggest single jobs the CP dicks ever handled was the opium smuggling aboard the company's luxury Empress liners before the war.

Normally, the railway cops have nothing to do with the CP steamships, but in this emergency, Inspector Walter E. Graham and a number of constables were loaned

to the steamship division.

The Empress ships were running from Vancouver to Honolulu, to Yokohama, to Kobe, to Shanghai, to Hong Kong, to Manila, and back.

Members of the crew were picking up so much opium in the Orient and dropping it at Honolulu that U.S. customs authorities were levying fines as high as

US$40,000 against the CP and even seizing their ships.

Graham and his men went aboard the ships as masters-at-arms in uniform and began a thorough checkup.

They contacted the special agents in the opium ports, fired all the known dope addicts from the native crews, and as much as possible cut down on gambling

among the crew members.

Besides this they searched the ships thoroughly every day while they were at sea.

"We looked everywhere, from the stokehole to the captain's cabin," Graham said in his slow deliberate voice.

"Behind the removable wooden panels was a good place to stow opium, so was unoccupied cabins. Even the officers' cabins were searched because the cabin

boys couldn't be trusted. The captain's cabin, for instance, they figured to be a pretty safe place to hide the stuff."

The smugglers used many stunts to get the dope ashore.

Sometimes the opium would be pitched over the side in watertight, buoyant containers to be picked up later by accomplices in small boats.

Other times it would be sunk with a long line attached to a small buoy for a marker.

Visiting relatives of the crew had to be watched particularly.

Do's and Dont's on the Road

So thoroughly was the lid clamped down on dope smuggling that in a year the price of opium in Honolulu rose from US$85 per five-tael tin to $250.

"Of course, that wasn't entirely due to our efforts," Graham explained.

"The agents in the ports, and the local police all worked with us, but I guess we helped some."

They must have helped some since they were officially commended by the Geneva Conference for setting a good example of dope traffic prevention.

Helping to watchdog celebrities is another of the railway cops' regular duties.

Whenever a visiting dignitary is travelling, such as the recent state visit of President Truman to Ottawa, extra police are on hand.

Of course the Mounties, and in the case of Mr. Truman, the FBI are also around, but the railway force must make sure that all railway employees who must be

there are bona fide employees and above suspicion.

The railway cop's job would be much simpler, and the public generally would be much happier, if people would observe a few simple precautionary measures while

travelling, Inspector Belanger maintains.

The most important of these are:

1. Have your initials or some other mark of identification on your luggage. That simple precaution will eliminate most of the mix-ups that cause so much

needless worry and work. Also don't leave your bags unattended in crowded stations and expect to find them when you get back.

2. Everybody, particularly women, should check their valuables before leaving washrooms. The police are always getting complaints from women who have taken off

rings, earrings, or watches and left them on the washroom shelf. The next person who comes along picks them up and there is little the police can

do.

3. Never play games for money with strangers on trains or ships. In fact, be wary of conversation with a stranger that gets around to money

matters.

4. Lock your hotel room door at night with the special little catch on the inside provided for that very purpose. Inspector Belanger explained that a favorite

mode of operation for hotel thieves is to take a room in a hotel, and then at about four o'clock in the morning, when everybody is sleeping most soundly, sneak

down the corridor and try the doors. About one in 10 is unlocked. The thief slips in quietly. If the owner wakes up he mutters something about "wrong

room," apologizes and gets out. If the guest doesn't wake up he steals everything but his gold teeth. "And if there is an empty crock on the dresser

it is just that much easier!" Belanger says. Another method is for the crook to register in one of the best rooms in the best hotel in town and during the

day have a duplicate key made for the door. Then he can come back when somebody else is occupying the room and go through his victim's effects at his leisure.

That's why it's a good idea always to place your valuables in the hotel safe.

5. Don't leave your wallet in your hip pocket and then hang your trousers folded over the hanger in your sleeping car berth. The wallet may fall to the floor

and you will never see it again. Of course if everyone took that excellent advice the railways could cut down on their police forces and a lot of cops would be

out of work. But, human nature being what it is, the railway police aren't worrying too much about that.

Max Braithwaite.

(because there was no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.