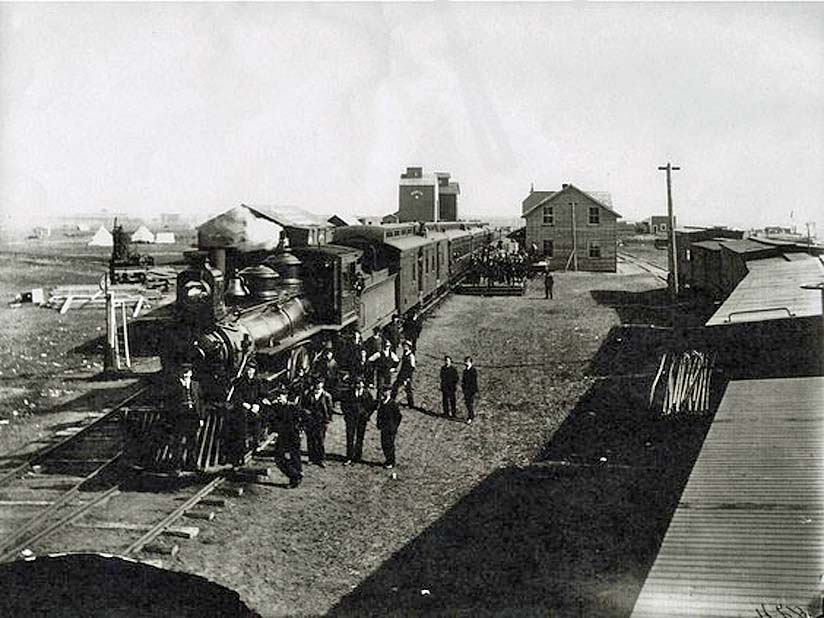

Saskatoon Saskatchewan - It could have been a scene from a movie about the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP).

After botanist John Macoun extolled the southern Canadian prairies as an agricultural eden awaiting the ploughing, James J. Hill, a member of the CP Syndicate,

pounded the map covered table with his fist and exclaimed, "Gentlemen, we will cross the prairies and go by the Bow Pass."

This decisive moment, captured by Macoun in his autobiography, profoundly altered Saskatchewan's development in the late 19th century.

But it is doubtful whether the spring 1881 meeting in Hill's office in St. Paul, Minnesota, ever happened.

Or that Macoun was responsible for the re-routing of the proposed transcontinental rail line.

Throughout the 1870s, it had been assumed that the CP mainline would travel through the North Saskatchewan country, the so-called "fertile belt," to

the Yellowhead Pass.

But in the spring of 1881, the Syndicate boldly decided to build directly west across the southern prairies through present day Regina, Moose Jaw, Swift

Current, and Maple Creek.

The route change, one scholar noted, "shifted the whole axis of development in the North-West."

Many reasons have been advanced for the abandonment of the Yellowhead route, and the over $4 million in survey work in preparation for

construction.

But the most common explanation was John Macoun's championing of the agricultural potential of the plains.

In "Men Against the Desert", for example, James Gray argues that, "It was Macoun's report to the Syndicate which helped guide the CP through the

southern Prairies."

Pierre Berton also highlights the St. Paul meeting in "The Last Spike", entitling a chapter subsection "How John Macoun Altered the

Map."

But did the meeting take place?

A faithful recorder of his activities in the field, Macoun makes no mention of it in his 1881 field notebook, 1881 diary, or correspondence for that

year.

Nor does he mention it in his massive Manitoba and the Great North-West (1882), a compendium of his activities in western Canada over the previous 10

years.

The James J. Hill papers, moreover, do not contain any reference to a meeting, or to Macoun in 1881.

In fact, the only account of Macoun's meeting with CP Syndicate members appears in his autobiography, dictated from memory some 40 years later, when the

botanist was nearly 90.

There's no doubt that the railway builders were aware of Macoun's highly favourable assessment of the southern prairies.

But the location of the railway had more to do with strategic business decisions than the quality of the land.

Ottawa's insistence that the CP follow an all-Canadian route made for engineering and construction challenges.

It also did not make business sense.

Building across the shield country north of Lake Superior and through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast would be expensive and time

consuming.

Nor would these sections of the line generate much traffic for the railway.

The losses from these non-revenue producing sections would have to be made up by the railway on the western prairies.

But that, too, was a problem from the outset.

The rail line was being built in advance of significant western settlement.

George Stephen, who headed the CP Syndicate, was concerned about these operational disadvantages.

During the CP contract negotiations, Stephen told Prime Minister John A. Macdonald that the Syndicate could probably "construct the road without much

trouble, but we are not so sure by any means about its profitable operation."

He was particularly worried about a rival U.S. line siphoning off prairie traffic and undercutting the costly Superior section.

"Now what do you think would be the position of the CP, if it were tapped at Winnipeg, or any other point west of that," Stephen asked the prime

minister.

"No sane man would give a dollar for the whole line east of Winnipeg."

The main line consequently was constructed as close to the international border as Ottawa would allow, even if it was not the best quality farmland, in order

to keep out American competition.

Branch lines would be built north to the Saskatchewan country (Regina to Prince Albert and Calgary to Edmonton).

A more southerly route, through the Kicking Horse Pass, was also necessary if the railway was going to capture all the traffic of the North-West and offset the

costs of operating the expensive Superior and Rocky Mountain sections.

As for John Macoun, he provided the agricultural justification for a route chosen for business reasons.

Meeting or no meeting, Macoun was not responsible for one of the most controversial decisions in Saskatchewan history.

Bill Waiser.

(because there was no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.