Calgary Alberta - Canadian Pacific (CP) is in the news this week with its historic US$25 billion purchase of U.S. railway Kansas City

Southern, which will create a 32,000 kilometre rail network, the first that would connect Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

Author, photojournalist, and former Calgary Herald journalist David Bly wrote the following historical piece, looking back at how the histories of Calgary and

CP are intertwined.

The story was first published in the Herald on 31 Aug 2008.

CP and Calgary have always had a symbiotic relationship.

Calgary was born when the Northwest Mounted Police established Fort Calgary at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers in 1875.

The settlement that grew up around the fort was what historian Henry Klassen called an "island community, isolated from markets in the east by

great distances".

The Hudson's Bay Company brought its goods to Calgary from Winnipeg by way of the North Saskatchewan River and the Edmonton Trail.

American traders had an easier time of it, bringing in goods from Fort Benton, Montana, on the Missouri River, but even that meant a 500 kilometre overland

haul.

Fort Macleod was the administrative and judicial headquarters for the region.

No one could have been faulted for assuming Calgary was destined to be little more than a small ranching town.

Then came the railroad, and that made all the difference.

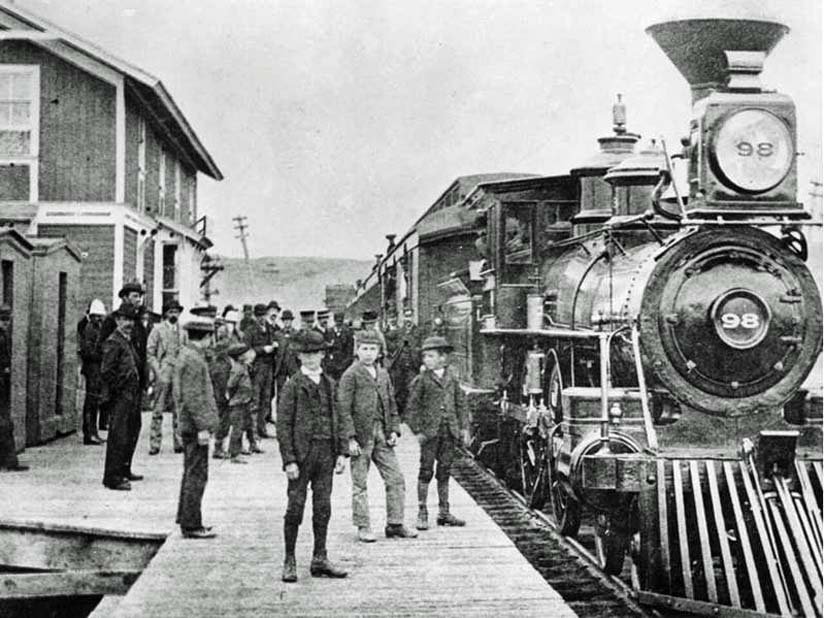

The first locomotive that chuffed into Calgary on the newly laid rails in September of 1883 signalled the beginning of Calgary's transformation.

Goods could now be brought in more quickly and at a lower cost.

Just as important, cattle and other agricultural goods could be shipped to the east.

The telegraph that came with the railroad brought instant communication.

Calgary was connected to the rest of the world.

"Changes in transportation and communications helped bring about developments in ranching, farming, manufacturing, and banking," writes

Klassen in "Eye on the Future: Business People in Calgary and the Bow Valley, 1870-1900".

"By 1900, the Bow Valley was producing more agricultural and industrial goods than any other region in Alberta."

The CP even shaped Calgary physically.

The seeds of the town had been planted east of the Elbow River, near Fort Calgary, but the CP decided the town's centre should be west of the

Elbow.

It built its station there and began laying out the streets that are now the downtown core.

Many existing businesses had to pack up and move across the river to be where the action was.

But Calgary was also a significant factor in the formation of the CP.

The transcontinental railway project got much of its impetus from George Stephen, president of the Bank of Montreal, and his cousin Donald Smith, a director

and major shareholder in the Hudson's Bay Company.

Each invested $500,000 in the CP.

The CP not only provided transportation and communication, it became a major employer in the city.

The railway's Ogden shops, used for overhauling and servicing locomotives and rail cars, became munitions factories during the Second World War, Allied

warships sailed the seas with guns made in Calgary.

However, the CP and Calgary had their conflicts.

By the 1950s, downtown Calgary was hemmed in by the rail yards on the south and the river on the north.

Many people resented the CP's swath of land that stretched through the downtown core, hindering traffic and development while generating little in

taxes.

Mayor Harry Hays approached the CP about moving the tracks, and in 1963, Hays and the CP announced a $35 million development that would see the main tracks

laid on the south bank of the Bow River in a transportation corridor that would also include an eight-lane expressway.

Enthusiasm abounded until city councillor Jack Leslie and others noticed the plan included no provision for doing away with the existing tracks and

yards.

It became apparent the deal was heavily in the CP's favour.

As cost estimates grew, so did opposition, CP finally told the city to take it or leave it.

In April of 1964, the city left it.

But interest in protecting the land along the river had been stirred, resulting in green development on the banks.

When the deal collapsed, one irate CP official told Leslie the railroad would never again do anything for Calgary.

Wounds heal though, in 1996, the CP moved its headquarters from Montreal to Calgary.

Ten years later, the CP donated its charter, one of the most important legal documents in Canadian history, to the Glenbow Museum.

The railroad is not visibly as much a part of Calgary as it was in the past, when the Calgary Herald would send reporters just to see who got off the train,

but its legacy lives on.

If the CP had chosen a different route to lay the tracks of its transcontinental railway, Calgary today would likely look more like Lethbridge or Fort

Macleod.

David Bly.

(because there was no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.