North America - Last Sunday, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) announced that it was purchasing the Kansas City Southern Railway

(KCS).

This is the first merger of big Class I railroads since 1996, and will form the first railroad company to span Canada, the United States, and

Mexico.

You might not immediately see the importance of this merger to Minnesota's economy, so let me put it another way.

Driving around Minnesota, you've probably seen a locomotive in white, red, and black paint.

It's associated with the SOO Line, a railroad that's been part of Minnesota's economy since the 1880s.

The SOO Line has been owned in part (and since 1990, entirely) by CP, which headquartered its U.S. operations in Minneapolis for over 120 years, until

now.

Thus, this merger marks the end of an era in Minnesota's economic history.

Let's explore that history and then examine how the merger could affect today's Minnesota economy.

James J. Hill and the Canadians

In 1878, James J. Hill laid the foundation for his Great Northern Railway when he and three Canadian partners acquired a bankrupt railroad, which they promptly

renamed the Saint Paul Minneapolis & Manitoba Railway Company (SPM&M).

By the end of 1879, "the Manitoba," as it was called, connected the Twin Cities with the Red River Valley and ran north to meet the newly chartered

CP.

The Manitoba soon became an efficient vehicle for delivering wheat from the plains of western Minnesota and eastern North Dakota to the growing flour mills of

Minneapolis.

Hill hoped that he could join with the CP to realize his dream of a transcontinental railroad from Saint Paul to the Pacific, but by 1883, he concluded that

cooperation with the CP was impossible.

In particular, the CP had become entangled with Canadian nationalism, and Canadian politicians wanted to avoid even the appearance of working with American

railroad companies.

Hill, who was a Canadian, and a director with CP, wanted the CP line to go south of Lake Superior through

American territory. The other CP directors decided to build the line within Canada so Hill quit CP and went his own way, to the benefit of America.

Hill, who was a Canadian, and a director with CP, wanted the CP line to go south of Lake Superior through

American territory. The other CP directors decided to build the line within Canada so Hill quit CP and went his own way, to the benefit of America.

Hill's Canadian business partners sold their shares in Hill's enterprise and the Canadian government made it clear that Hill could not connect the Manitoba

to the new Canadian transcontinental.

Hill ultimately decided that the best course was to build his own transcontinental along his preferred route from Grand Forks due west to the

Pacific.

In the mid-1880s, Hill began the project by extending the Manitoba line west to the rich mining districts of western Montana.

He then built the renamed Great Northern Railway westward from Montana and eastward from Seattle, Washington, completing the project in 1893.

SOO Line a Railroad of Their Own

The millers of Minneapolis watched the growth of Hill's railroad with increasing concern.

Yes, the Manitoba efficiently ferried wheat to the Minneapolis mills, but Hill developed greater and greater control over this trade in the late 1870s and

early 1880s, so the millers worried that Hill would soon raise his rates.

Millers had to ship their finished products east via Chicago and this route was controlled by other existing railroads that had already raised rates and cut

into their profits.

Hill might just do the same.

In response, "prominent Minneapolis businessmen," such as William D. Washburn (milling), Thomas Lowry (real estate), and Charles Pillsbury (milling),

"founded the railroad, originally called the Minneapolis Sault Ste. Marie & Atlantic, in 1883."

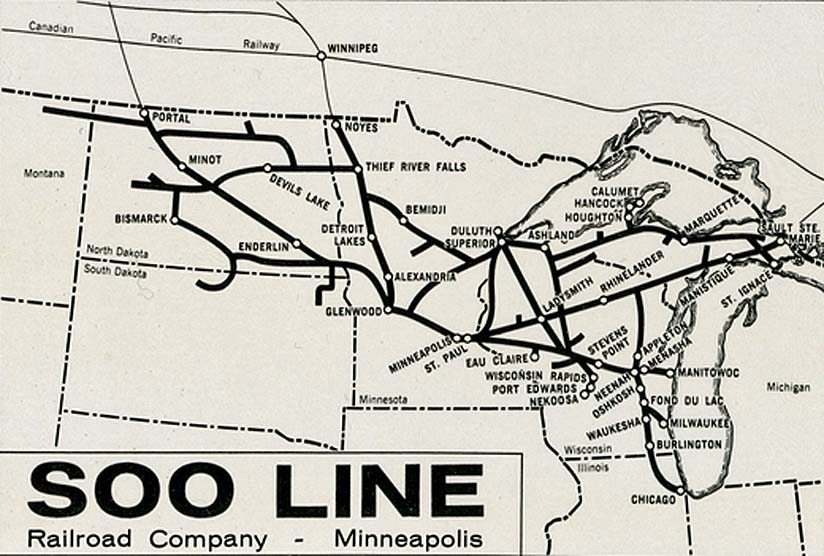

The SOO Line, as it came to be known, bypassed Chicago by connecting the Twin Cities with Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Flour could then be shipped eastward on a combination of Canadian and American rail carriers.

Further, by building their own lines from Minneapolis westward towards North Dakota, the millers could break Hill's hold on the wheat trade.

Thus, the SOO Line developed a very successful V-shaped route that connected Sault Ste. Marie in the east, Minneapolis in the middle, and northeastern North

Dakota in the west.

Return of the Canadians

Meanwhile, back in Canada, CP had finished its rail line from Toronto to Vancouver via the north side of the Great Lakes.

However, sober analysis showed that the SOO Line's path was superior to the CP's unpopulated northern trackage.

At the same time, the managers of the SOO Line knew that most of the freight they delivered to Sault Ste. Marie went east on the CP and that, with a bit of

construction, the western end of the SOO Line could connect to the CP's western route.

The Canadians and the Americans thus struck a deal.

CP bought 50 percent of a reorganized SOO Line, and the SOO Line became the American arm of the CP, operating as an independent company until 1990 when

CP took 100 percent control.

Over the years, the SOO Line name disappeared from locomotives and rolling stock, replaced by CP's logo.

In 2012, the CP moved out of the SOO Line Building and took over the former headquarters of the First Bank System, now called Canadian Pacific

Plaza.

In summary, the Canadians made a mistake when they rejected James J. Hill's overtures to connect his railroad with the CP.

I doubt any Canadian today would ever say that building north of the Lakes was a mistake!

I doubt any Canadian today would ever say that building north of the Lakes was a mistake!

The SOO Line was built in response to Hill's growing power in railroading.

And the CP rectified their error in rejecting Hill's original offer by buying into the SOO Line.

Effects on Minnesota

Today, The CP/KCS merger is premised on growing trade among the members of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), building on the progress already

made under the previous trade pact, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Minnesota's products could, in theory, stay in the same container, hopper, or boxcar all the way to Mexico City, or any point in between on the new rail

network and gain from this expansion of trade.

Further, the KCS connects to ports on the Gulf of Mexico, and thus provides an alternative to other railroads for Minnesota farmers and manufacturers shipping

their products abroad.

In the long run, the merger could keep transportation costs down for Minnesota shippers.

On the other hand, the merger might hurt the Twin Cities economy, at least a bit.

Minneapolis has been the headquarters for CP's US operations since 1888.

According to the merger announcement, "Kansas City, Missouri. will be designated as the U.S. headquarters," but "CP's current U.S.

headquarters in Minneapolis-St. Paul will remain an important base of operations."

We don't yet know what this means, but one possible effect is a loss of Minnesota-based jobs that move to Kansas City and other points on the KCS

system.

Either way, the SOO Line will continue to be part of Minnesota's economic story.

Louis D. Johnston.

(because there was no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.