Gatineau Quebec - Today, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) released its Investigation Report R19W0002 into a collision involving two Canadian National Railway (CN) freight trains near Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.

Links to Transportation Safety Board (TSB) Investigation Reports

are no longer provided as they keep changing their report address (URL). Manually search for the Investigation

Report number indicated above.

Links to Transportation Safety Board (TSB) Investigation Reports

are no longer provided as they keep changing their report address (URL). Manually search for the Investigation

Report number indicated above.

As a result of the investigation, the Board is issuing two recommendations to Transport Canada (TC).

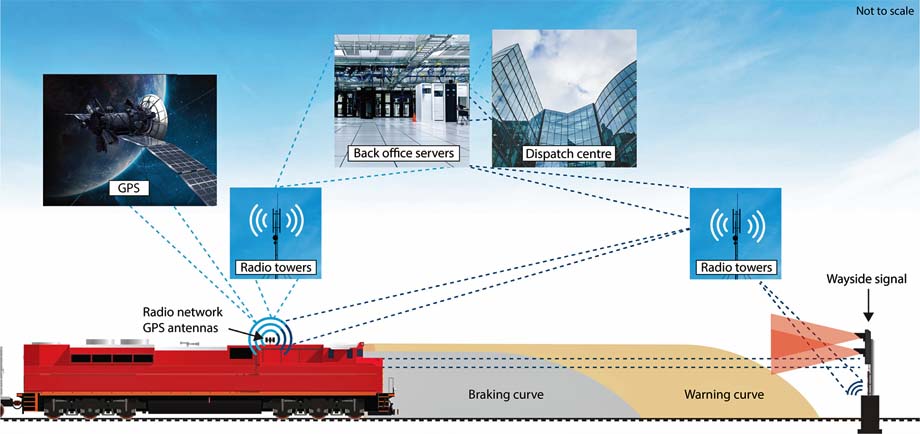

First, the Board recommends that TC require all major Canadian railways to expedite the implementation of physical

fail-safe train controls on Canada's high-speed rail corridors and on all key routes.

"The United States has fully implemented a Positive Train Control (PTC) system on all high-hazard track required

by its federal legislation.

This includes the U.S. operations of both CN and CP, which have invested significantly in their locomotive fleets and

infrastructure," said TSB Chair Kathy Fox.

"The railway industry must act more quickly to implement a similar form of automated or enhanced train control

system on Canada's key routes to improve rail safety and avoid future rail disasters."

Second, the Board recommends that TC require Canadian railways to develop and implement formal crew resource management

(CRM) training as part of qualification training for railway operating employees.

"The aviation and marine industries experienced significant safety benefits with the introduction of CRM,"

said TSB Chair Kathy Fox.

"This type of training could provide additional tools and strategies to train crews to mitigate inevitable human

errors, providing significant safety benefits in the rail industry."

The Occurrence

On 3 Jan 2019 eastbound CN freight train 318 collided with the side of westbound CN freight train 315 just east of

Portage la Prairie, Manitoba.

At 06:10, train 318 departed Rivers, Manitoba, towards Winnipeg.

At about 07:30, westbound train 315 departed Winnipeg.

Both trains were operating on the Rivers Subdivision, one of CN's busiest routes which frequently transports dangerous

goods.

Just under 3 hours later, while proceeding on the south track using Trip Optimizer (a system similar to cruise control

on a car), train 318 passed a signal at Mile 52.2 indicating to the crew that they should be preparing to stop at the

next signal, located at Mile 50.4 at Nattress.

The conductor called out the signal as required, but did not hear the locomotive engineer (LE) verbally respond and the

train continued at track speed.

Soon after, the head ends on train 318 and train 315 passed each other, and train 318's conductor reminded the LE of

the previous signal.

The LE then applied the train brakes.

However, as the Stop signal indication at Nattress came into view, the crew recognized that they would not be able to

stop in time and applied the brakes in emergency.

Shortly after train 318 collided with the side of train 315 at 23 mph (37 kph), the crew jumped from the train,

sustaining minor injuries.

The two head-end locomotives on train 318 and eight cars on train 315 derailed as a result of the

collision.

Investigation Findings

The investigation determined the following:

The crew on train 318 had formed the expectation that they would continue following behind an earlier eastbound train

through to Winnipeg, without stopping at Nattress.

The LE was fatigued due to disrupted sleep periods during the 2 nights preceding the accident.

Consequently, he experienced decreased vigilance due to fatigue and the reduced workload associated with the use of

Trip Optimizer which contributed to his delayed reaction to the signals displayed in the field.

Railway operations rely predominantly on administrative defences, such as Canadian Rail Operating Rules and Work/Rest

Rules for Railway Operating Employees, and safe train operations are contingent on train crews following the

rules.

When a train crew does not follow the rules, for whatever reason, the administrative defences fail.

When there is no secondary physical fail-safe defence, such circumstances can result in an accident that otherwise

could have been prevented.

The train 318 crew communication within the cab was ineffective.

Due to the difference in the level of experience between the train 318 crew members, the conductor deferred to the LE

without questioning the operation of the train, and as a result, the crew's actions to slow and stop the train were

delayed.

This accident highlights major issues in the rail industry and reinforces TSB's call for physical fail-safe train

controls for over two decades through recommendations R13-01 and R00-04.

The issues identified in this investigation also highlight two recurring TSB Watchlist issues, following railway signal

indications and fatigue management.

Following this occurrence, CN distributed a System Notice throughout its Canadian operations warning train crews that

there was an increase in occurrences where train crews failed to stop at signal indications requiring them to do so,

primarily due to a lack of focus on situational awareness.

Author unknown.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.