The Canadian Prairies - Trains were the only practical way to move people and goods until the

arrival of all-weather roads in the 1950s and 1960s.

From when the last spike was driven to complete Canada's trans-continental railway in 1885 to today, the country's

rail system has been the linchpin holding the nation together while opening up the Prairies for settlement by

farmers.

But as much as the railway was needed to open up agriculture in the West, the railway needed farmers and ranchers to

maintain profitability by shipping and receiving the fruits of their labour, said Stephen Yakimets, president of the

Alberta Railway Museum.

"Until the 1950s, you didn't have all-weather roads, so to get the various goods you would buy you'd order them

from the catalogue and they got shipped by rail to the local town. It was a case of co-dependency. The railway takes

away your raw materials and you purchase materials that come on the railway. It was really a conduit for agriculture in

Western Canada," he said.

One couldn't survive without the other, said Yakimets.

"I don't think you can overstate it. It was the only real way of moving goods and people from the time the

Canadian Pacific Railway went through until the 1950s, 1960s, when you started to get all-weather roads and even into

the 1970s you still had a lot of gravel roads out there. For that whole farming economy, it was, how do we get

everything from plows to clothing? Everything comes through the railway and comes to our little town," he

said.

Conversely, it was the only way to move out product in bulk, and still is in many cases, he said.

In the early 20th century, there was plenty of investment in advertising Western Canada for settlement throughout

Europe, with rail companies using demonstration farms to advertise the bounty of the land, which was inexpensive or

even free.

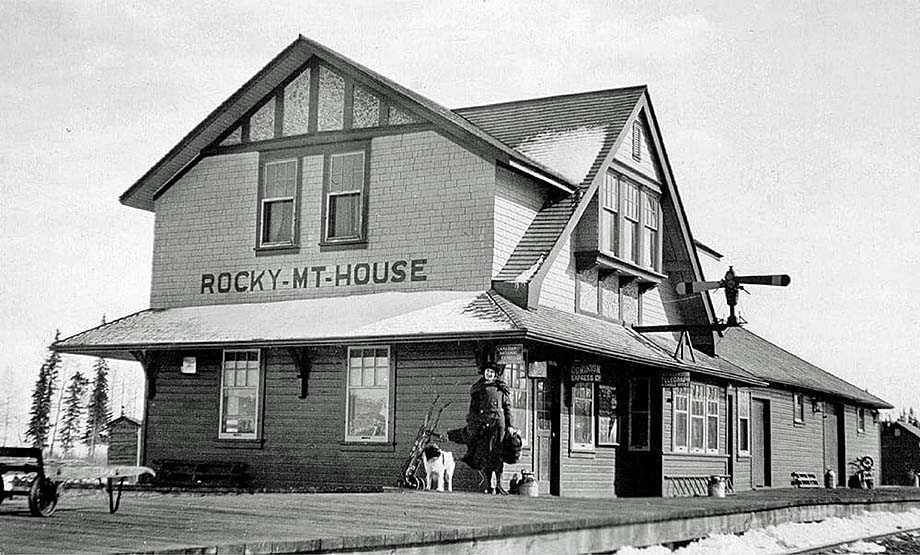

But the train represented even more to many communities, the local station was home to all the comings and goings in a

town, representing a communication network that brought the latest news from afar in an age before the internet and

even before telephones became commonplace in households.

In their time, the railway companies held ultimate sway where a community would be located.

"The railway stations developed the townsites," he said, stating the rail companies would bypass land

speculators by simply moving the station further down the line.

"And you see this history of small communities moving on wagons to where the railways were. The railways were in

this to make money, so wouldn't go to where people set up their own towns, but they would go to their own sites so

they could sell lots there."

Communities followed a standard layout, said Yakimets, in which a railway street or avenue would run parallel to the

tracks and a main street would run perpendicular near the station.

But as quarter-section farms have turned into much larger operations, there is no longer a need for so many stations,

said Yakimets.

The situation has seen many branch lines torn up, which has also corresponded with the decline of the populations of

towns.

But for the Ogema, Saskatchewan-based Southern Prairie Railway, the preservation of the tracks has led to a

community-owned line to serve local farmers while preserving the history of rail in the province.

"We were the first community-owned shortline. We have 150 shareholders," said Carol Peterson, Southern

Prairie Railway chair.

Their railway is one of 11 in the province.

Peterson said in 1998, a group of farmers got together to buy the line from the Canadian Pacific Railway.

"Their motto is "our way or the highway"," said Peterson of the Redcoat Road and Rail, which runs

the 115 kilometre line between Pangman and Assiniboia, and is part of the Great Western Railway network.

Southern Prairie Railway operates the historical arm of that span of track, running tours in the summer on the

weekends.

While towns have seen their populations decline with the loss of railways, Peterson said the 400 person community of

Ogema draws a crowd for excursions on the line, creating jobs and prosperity to local businesses with more than 4,300

visits in 2023.

Like Yakimets, Peterson said there wouldn't have been a Canadian West without the train, and Southern Prairie Railway

has recently won awards for its sharing of the history of rail in Saskatchewan.

"We won two awards in October and November about living history because we explain how the settlers came to

Saskatchewan, southern Saskatchewan in particular, and how they lived, worked, and played," said

Peterson.

As for the future of rail in the West, she can't see a return to the heady days of widespread passenger traffic by

train in Canada, noting much of the infrastructure has been lost and the cost to rebuild it is

prohibitive.

"They should never have taken the rail lines out," said Peterson, noting Ogema's original station was

demolished.

"We didn't have a train station from the 1960s until 2003, when we moved the one from Simpson to Ogema. There was

something missing at the head of Main Street because there was this great big empty space. Putting the train station

back in there just pinned the space."

While some communities have been lost as the rail line has disappeared and the Trans-Canada Highway bypassed them, rail

continues to be a major player in transportation in Canada, generating more than $10 billion annually, according to

Transportation Canada.

Alex McCuaig.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.