RAILROAD

Provo Utah - From 1899 until 1967, a shortline railroad (its official name was Utah Eastern Railway) ran between Provo and Heber City via Provo Canyon.

It made slow trips, the urban landscape in Provo, and the steep grades and curves in the canyon rendered speed impossible.

In fact, the engine fairly crawled over some stretches at 20 miles per hour or less, giving the line its nickname, the Heber Creeper.

The Heber Creeper seemed destined for slowness even before the railway came into existence.

The idea for a line through Provo Canyon was conceived almost 50 years before labor on the track began.

Soon after the first Mormon settlers arrived in the Great Basin in 1847, Brigham Young and other church leaders expressed enthusiasm for the construction of a transcontinental railroad through Utah Territory.

In 1852, the Utah Territorial Legislature voted to send a memorial to the United States Congress asking for the passage of a bill that would encourage construction of a railroad to the Pacific Ocean.

Utah leaders were of the opinion that the best route for the line led through Provo Canyon.

Mounting problems between the Northern and Southern states, and the resulting Civil War, slowed construction of the transcontinental railroad.

When track laying finally picked up steam after the war, a route was surveyed and constructed through Weber Canyon instead of Provo Canyon, making Ogden the railroad center of Utah.

Despite the fact that Provo had been snubbed, railroad enthusiasts didn't give up easily.

The idea of a rail line through Provo Canyon just kept creeping along.

In 1874, an English company contemplated laying track through the canyon and beyond, to Coalville in Summit County.

From there, the line would transport coal to urban areas.

But the plan withered in its formative stages, and the company built no line.

Mining companies eventually sent the coal to Ogden over the transcontinental line, and it came to Utah Valley via Salt Lake City on two locally constructed lines, the Utah Central and Utah Southern railroads.

A Sneaky Survey

None of the schemes promoting a railroad through Provo Canyon materialized until April 1896.

That year the Salt Lake Tribune reported, "A gang of surveyors... who are exceedingly mum and refuse to say for whom they are working, are establishing what appears to be a grade for a railroad through Provo Canyon."

Travelers through the canyon confirmed the newspaper's report.

The mysterious surveyors turned out to be employees of the Rio Grande Western Railroad Company, and even though the company denied it was scoping out a railroad grade, that is in fact what it was doing.

The tentative line through Provo Canyon terminated at Park City.

The possibility existed that a line might later be extended from there to the Uinta Basin.

Provo's Daily Enquirer worried that the company had no intention of laying track, but only staked its claim to the route to keep other railroad companies from constructing lines through the canyon.

These fears proved groundless.

The Rio Grande Western hired the Springville company of Deal & Mendenhall to spearhead construction.

Preparation of the track bed and the laying of rails proved to be a lengthy process.

The precipitous, narrow, canyon retarded the progress of the grade builders, but their most toilsome task was bulldozing past a man named Nunn who was not in the habit of being pushed around.

Industrial Vision

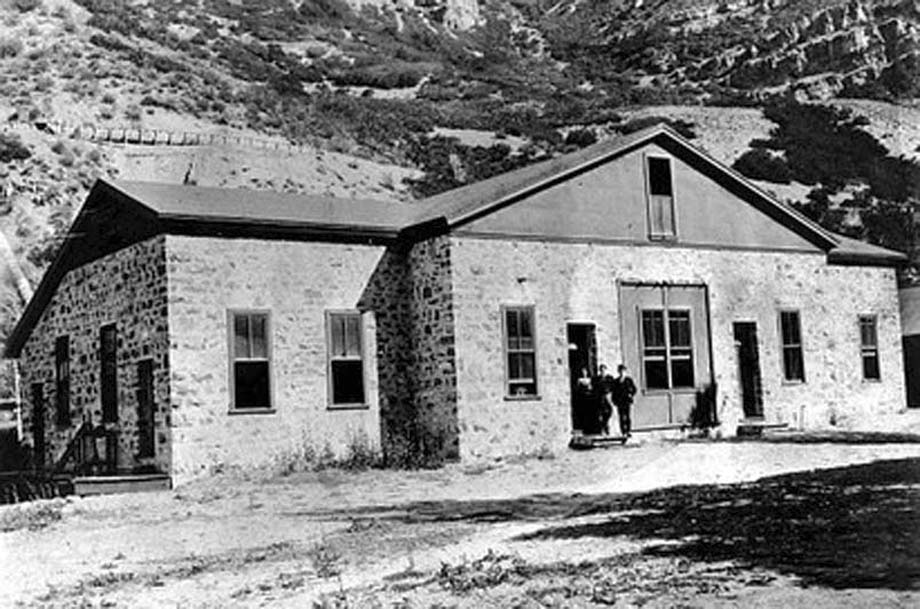

In 1896, L.L. Nunn and the Telluride Power and Transmission Company, planned the construction of a hydroelectric power plant on the Provo River just below Bridal Veil Falls.

They intended to build a small, temporary, power plant, later named Nunns, and to create electricity with water carried to this plant by way of a flume.

The company planned to build a power line from Nunns to Mercur, a boom town in the Oquirrh Mountains northwest of Provo, and other mines located in the western mountains.

Workmen would also use some of the Nunns electricity to help build a larger, permanent, power plant near the mouth of Provo canyon.

To provide water for the larger plant, which the company named Olmstead, Nunn planned to build an 80-foot-high dam across the Provo River near Upper Falls.

This idea met with some opposition.

The dam would make it necessary for the railroad company to build its grade high up on the mountainside, a job that the Rio Grande Western considered to be too costly and difficult.

Also, many people in Provo worried that a high dam would be a danger to the community.

If it collapsed, much of the town might be washed away.

The railroad company and the power company both claimed to own right-of-way near the dam site.

In September 1896, a judge injoined the Telluride Power Company from doing further grading for the Rio Grande Western in that area.

Deal & Mendenhall moved its men a little farther up the canyon and continued working, but no more grading could be done in the area of the dam site until the problem with the right-of-way could be solved.

Two long court cases ensued.

Provo Controversy

Meanwhile, the people of Provo found themselves in a bind.

They wanted and needed both the large power plant and the railroad to Park City.

However, Provo's Utonian reported, "If we are to lose one it had better be the power plant, as it is believed that while both will be advantageous and profitable to the community, the greatest good to the city will result from the operation of a railway between Provo and Park City."

This appears to have been the opinion of the majority of Provo's population.

As its lawyers fought the court case with the power company over the right-of-way, the Rio Grande Western moved ahead with its scheme to build the line to Park City.

Initially, the company planned for the line to skirt the western edge of Provo and then run northeastward to the mouth of the canyon.

At the time, some of Provo's mill owners and other influential citizens whose manufactories were established along the millrace on 200 West convinced the railroad that a line up 200 West would be beneficial to everybody.

The Rio Grande Western petitioned Provo for a franchise permitting it to run its tracks along 200 West.

The company also asked the city to grant it some land on University Avenue and 600 South for a depot.

These requests stirred up a hornets' nest in Provo.

The Utonian favored the 200 West route.

It pointed out that a line on that street would stimulate manufacturing, and property values in the area would rise.

The newspaper promoted the idea that if the railroad company would grade 200 West and the crossings, the road would become "a far better street for general travel than it is today."

Provo's other newspaper, the Daily Enquirer, took the opposite point of view and effectively countered the Utonian's opinions with sarcasm.

The Enquirer marveled at what a unique idea it was to divide the city with "a living, rumbling, smoking, rattling, tooting, line that will not let the east ender nor the west ender forget for a moment that Provo was once a city."

About the citizens who lived along 200 West, the Enquirer wrote, "They have slumbered as long as Rip Van Winkle to the rhythmic lullaby of the mill race. The clangor and rush of a dozen trains at night will give a new and lively turn to their dreams."

Permission Granted

The Enquirer went on to say that having the train cross 12 streets a dozen times a day would give "72 opportunities not now enjoyed of training our teams not to be frightened of the car!"

Perhaps 72 times more railroad accidents would happen.

That would help make the "daily papers bright and sparkling."

Citizens held a mass meeting to discuss granting the railroad a right-of-way on 200 West.

The City Council debated the idea in public meetings.

Finally, in mid-March 1897, the council granted the railroad's petition, and surveyors rapidly went to work on the route through town.

On 16 Apr 1897 the court ruled on the first railroad right-of-way case.

The decision awarded the Rio Grande Western the route through Provo Canyon.

Telluride Power Company immediately appealed the decision to the Utah State Supreme Court.

Provo residents received some disquieting news in June 1897.

They learned that the Rio Grande Western had purchased the Utah Central branch line from Echo Canyon to Park City.

Now it appeared that there would be no need for the Rio Grande Western to build the line through Provo Canyon.

Fears that now no canyon railroad would be built were somewhat allayed in early August when rails, spikes, and ties began to arrive in Provo.

By the end of the month, workmen, many of whom were from Provo, started laying track on 200 West.

Provo City and the Rio Grande Western worked together to improve 200 West.

The city graded the street and filled low spots with gravel.

By early September, the Utonian reported that the street was "already in better condition than it has ever been."

Unfortunately, a soggy acident in early October 1897 caused the road to rapidly revert to its former condition.

At the woolen mill, located on 200 West between 100 and 200 North, a weir backed up the millrace for several blocks, creating a large pond.

Water from the pond was channeled through a water wheel that powered the mill's equipment for making cloth.

The railroad company had planned to build a rock retaining wall along the stream to protect the railroad tracks from possible floods.

The wall was to be 12 to 14 feet high near the water wheel, and would then taper to a height of about 8 feet as it extended northward.

The Rio Grande Western shipped in 30 carloads of rock from Spanish Fork Canyon to build this block-long wall.

The Call of Lunch

Laborers busily dug away the high clay stream bank to within 2 feet of the millrace to prepare for the construction of the wall.

They had just finished trimming the bank at its highest point near the mill's water wheel when the noon whistle blew.

The men quickly left their work in search of lunch buckets.

Only one small girl who lived in the neighborhood remained at the site.

What she observed may have reminded her of the Biblical flood, only without two of every animal.

Water pressure against the highest point of the clay bank caused it to give way, and a torrent gushed down 200 West, washing away the sidewalk, track bed, and the newly improved road.

Flood waters coursed down 200 West to 100 South where some of it cut through to 300 West and ran southward to 300 South.

At some points, it nearly flowed into people's houses.

A small lake formed on Center Street between 200 and 300 West, tempting local businessmen to close shop, grab poles, and go fishing.

Much of the water ran down 200 West and eventually found its way back into the millrace.

Road conditions in that part of town quickly returned to circumstances like those experienced during pioneer times.

The Daily Enquirer reported, "Travel on H street (200 West) between 7th and 10th (Center and 300 North) is impossible as there is now no road."

The watermaster turned off the flow in the millrace, and railroad laborers repaired the break in the ditch bank.

While the water was off, the woolen mill switched from water power to steam power generated by its coal-fired boiler.

When the destruction caused by the flood was finally repaired, damages totaled several hundred dollars, a fair sum in those days.

Finally, in December 1897, Utah's Supreme Court confirmed the decision of the district court dealing with the first right-of-way case, but the second case was not settled until May 1898.

The railroad company constructed about one mile of track between 1897 and early 1898, but it made no further significant progress on the line until early in 1899.

A Dollar a Day

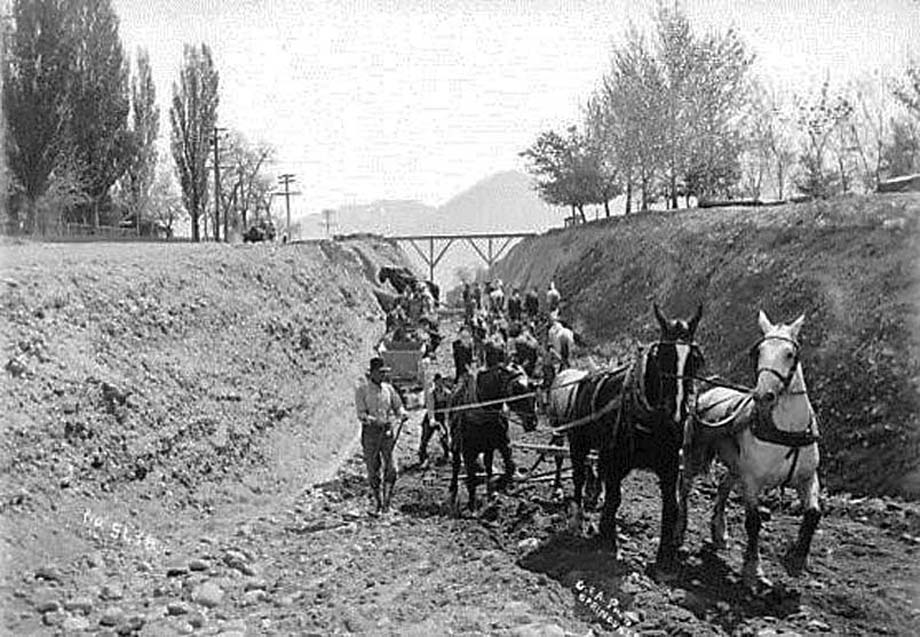

In March 1899, the Rio Grande Western finally awarded contracts for a grade from Provo through the first 10 miles of Provo Canyon.

Deal Brothers & Mendenhall of Springville got the contract.

It paid its subcontractors by the day.

A man received $1, a man with a team got $3.50, and a man with a wheel scraper was paid $4.

The contractors made good progress early in 1899.

Track crews began working in Provo during March.

They replaced the temporary iron rail on 200 West with steel track.

Carpenters built two bridges over the millrace.

By April, workmen had completed the six miles of grade extending to the mouth of the canyon.

Less than a month later, bridge builders completed a structure across Provo River at the mouth of Provo Canyon, and by the end of May workers had completed laying rail to the mouth of the canyon.

Work trains transported spikes, ties, and rails to the end of the line.

After three years of planning, and with work slowed by lawsuits and local disagreements, the Rio Grande Western readied its workmen for the assault on Provo Canyon, the most formidable physical obstacle on the route to Heber.

D. Robert Carter.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

(the image is altered or fake)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.