RAILROAD

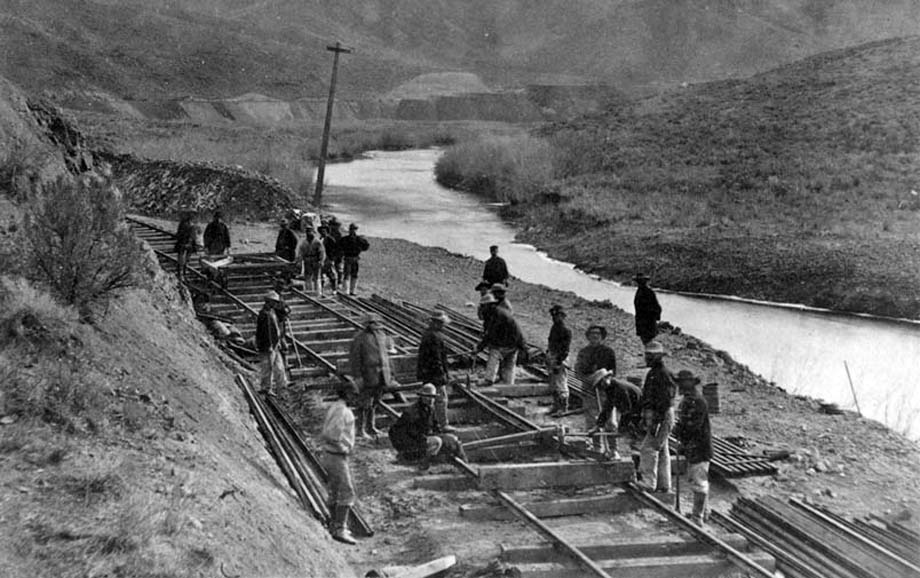

Provo Canyon Utah - During the spring of 1899, the Rio Grande Western prepared to lay the final stretch of track that would connect Provo with Heber City.

It had already laid the rails down Spanish Fork Canyon, through Provo and onto Salt Lake City.

Constructing the branch line through Provo Canyon to Heber City, grading the road bed, and laying track, would be risky business.

Four serious accidents occurred in the canyon, one of them fatal.

The first incident to attract the attention of local newspapers occurred on 11 Apr 1899.

A.B. Lawrence, superintendent of buildings and bridges for the Rio Grande Western, was riding his horse along the railroad grade when the animal stumbled and fell.

The horse fell on Lawrence's leg, and its weight broke both leg bones just above the ankle.

Since the superintendent traveled alone, he lay helpless for quite some time before being discovered.

After what must have seemed like hours, Lawrence spotted a man in a wagon passing by not far away and hailed him.

Isaiah Lott heard the cry for help and found the injured man.

Lott loaded Lawrence into his wagon and took him to Provo where Dr. S.H. Allen set the bones.

The Daily Enquirer described the torturous bone-setting process, "Mr. Lawrence went through the very painful ordeal without anesthetics, sighting down along his limbs to help line them up. His practical eye told the doctor when the bones were in place."

According to the newspaper, Lawrence recuperated in the Hotel Roberts until his leg was well enough healed to allow him "to be around again."

A much more serious accident took place on 17 Apr 1899 near the current Provo City Park at Nunns where a small power plant was located.

Peter McGovern, a 45-year-old Kentuckian who had lived in Springville for three or four years, worked near the railroad grade.

Two Springville youths, Arthur Bird and a boy named Deal, who was the son of one of the grading contractors, sat in a wagon nearby.

All three worked for Deal Brothers & Mendenhall.

Above the three workers and some distance away, Sidney Belmont, a stone contractor from Provo, and a gang of his men set a heavy charge of powder in an outcropping of rock.

Belmont was quarrying stone that he intended to use in building the abutment for the nearby railroad bridge across the Provo River.

While Mike Gillen prepared the shot, Belmont sent Bert Stubbs over the hill to tell the grading men in the cut that the blasters would soon fire a charge.

McGovern and the others wanted to know if the shot would use black powder or an improved, more powerful, formula.

He also wanted to know where it was being placed so he'd know whether to take cover.

While Stubbs informed workmen in the cut, Belmont walked around a ridge to where some company carpenters were working and told them of the imminent blast.

As the carpenters left the area, they moved through the cut where the graders worked.

They also informed the laborers for Deal Brothers & Mendenhall that the blasters were about to set off a shot.

So everyone seemed to have been duly informed.

Bad Luck

Just before the fuse was lit, Belmont yelled down the mountainside to the graders below that the men above were about to shoot.

The graders apparently felt they were safe in the cut, for they did not move.

They probably would have been unharmed if they had remained close to the vertical wall on the side of the explosion, but McGovern and the others remained in the open.

When McGovern heard the blast, he looked up into the sky.

A falling two or three pound rock struck him directly in the forehead, fracturing his skull, lacerating his scalp and face, mashing his nose, and cutting his upper lip in two.

A smaller rock hit the horse that was hitched to the wagon in which the two Springville boys sat.

The animal plunged forward, throwing Bird out of the wagon, and the boy received cuts and bruises on the head and limbs.

Young Deal escaped injury.

Provo's Dr. Allen hurried to Provo Canyon to treat the injured workmen.

He judged McGovern's skull fracture to be the worst he had ever seen.

The doctor found it necessary to operate on what the newspaper referred to as the "mashed in" forehead of the victim and remove large pieces of bone from his brain.

The patient remained delirious most of the time and did not remember how he had been injured.

He said that he was chopping down a tree and a splinter flew in his eye.

Utah County Sheriff George Storrs drove up the canyon to transport the wounded man back to the valley.

Storrs took McGovern to the home of Mrs. Leah Pyne where he received further medical attention.

Arthur Bird returned to his home in Springville and recovered rapidly.

Representatives of Deal Brothers & Mendenhall met with Belmont and Utah County officials to negotiate who would pay for McGovern's medical expenses.

The two construction concerns decided that they would share the costs.

Surprisingly, McGovern's condition improved, and Dr. Allen began to believe that his patient just might live.

A mere nine days after the accident, Allen declared his patient to be on the high road to recovery, even though McGovern had not yet recovered full consciousness.

On 28 Apr 1899 the Daily Enquirer reported that McGovern, his face still swathed in bandages, was walking around the streets of Provo, though his mind was "somewhat affected."

In the next several months it became clear that Peter McGovern's mind was "not at all clear," and the local newspaper wrote that it appeared uncertain that he would "ever regain his mental faculties."

In August, "Pete" received a 20 day jail sentence for cutting a bicycle tire in two.

During the trial, McGovern conducted his own defense.

He said he did the deed because "he wanted to see the tire explode."

The Daily Enquirer reported that he hoped to find dynamite in the tire and "was surprised to find only wind."

Things went from bad to worse for McGovern, who suffered continuously from headaches.

He had been known to carouse with Bacchus in the past, but now, possibly in an effort to reduce his anguish, he gave himself completely over to drink.

The inebriate developed a mania for lining up telephone poles, and he became extremely loud and abusive about their condition if they were crooked.

One day he stood in front of an upstanding citizen of Provo's LDS Second Ward as if to line him up.

That's when Provo's law enforcement officials concluded that it was time for a mental evaluation.

Dr. Robison, the county physician, and Dr. Pike assessed his case and committed McGovern to the State Insane Asylum in Provo.

Authorities released McGovern a short time later in hopes that he could cope with normal life.

He returned to Springville, but it soon became clear that the man still needed supervision.

Springville law enforcement officials sent him to the county jail in Provo.

It appears that the law enforcement officers at the jail sent McGovern to the Utah County Infirmary, which was located on the old highway between Provo and Springville.

At this point, news relating to McGovern disappears from the newspapers.

Apparently, the unfortunate laborer did not die in Utah.

It is possible that he may have returned to his relatives in Kentucky.

Another Blast

In May 1899, a second blasting accident occurred in Provo Canyon.

This mishap, however, was connected to the construction of the power plant.

The low dam that the power company had built near Upper Falls made it very difficult for trout to go upstream to spawn, and it was necessary to build a fish ladder over the dam.

Henry Arrowsmith, an employee of the Telluride Power and Transmission Company, and several other men, worked on that fishway.

The crew found it necessary to blast out several large boulders lying in the river bed.

The explosion sent a rock flying through the air.

The projectile hit Arrowsmith in the small of the back, throwing him to the ground, breaking the skin, and leaving a severe bruise.

It took awhile for him to catch his breath.

Fortunately, the rock broke no bones.

Arrowsmith's fellow workmen loaded him into a wagon and drove him to his home in Provo.

The Daily Enquirer reported that within a week he was "able to be around again."

More Accidents

Toward the end of May 1899, yet another construction accident occurred.

James Murphy, a son of the Emerald Isle, worked on Henry Sumpsion's gang as a grader in Provo Canyon.

The crew he worked on safely fired a blast and began to remove loose rock from the hillside.

Murphy's foreman, a man named Wall, laboured toward the top of the slope.

He tugged at some brush and dislodged a large rock which tumbled down the mountainside.

Murphy was bent at work squarely in the path of the bouncing boulder.

It nicked his shoulder and landed directly on his right foot, smashing it into a pulp.

Dr. Allen received a call once more and hurried up the canyon.

He found it necessary to amputate the injured man's foot as far back as the heel.

When Murphy was transported to Provo the next day, he was still in great pain.

On the bright side, the Daily Enquirer stated that the Irishman was "thankful that the stone did not strike him on the head."

The last major accident associated with the construction of the railroad line between Provo and Heber City happened on 12 Jun 1899 near Upper Falls.

The ill-fated workman was a 20-year-old, part-Indian, from Sevier County whose true name was said to be Zane Hill.

That was not the name to which he answered, however.

For several years, he had lived with an Elsinore farmer named Peter Madsen.

Apparently out of admiration, Hill took the name of his benefactor, and from that time on he went by the alias of Peter Madsen.

The construction company, whose camp was located on the north side of Provo River, used a small skiff to ferry Madsen and the other workmen to the south side of the river to work on the railroad grade.

The hearty graders crossed the thunderous water four times a day.

Each crossing was no small task, since the river ran exceedingly high and the water crashed powerfully down the canyon.

The Daily Enquirer wrote concerning the river's velocity, "With mighty force it comes dashing down the canyon, rolling large rocks in its course, a truly vicious stream."

A savage stream it proved to be indeed.

Madsen and the other workmen safely crossed the river early on the morning of 12 Jun 1899 and worked until 11:45, when it was time to return to camp for lunch.

Nine men had already safely made the trip before Peter Madsen and another grader boarded the skiff and the ferry man began winching the boat toward the north bank.

As the skiff neared the docking point, it suddenly dipped to one side.

Madsen became alarmed and leaped from the boat into the water.

In desperation, he grabbed the pulley rope.

This made it virtually impossible for the ferryman to move the skiff.

Workers on the shore did everything in their power to save the panic-stricken man.

Just as Madsen was almost within their grasp, his tired hand lost its grip on the ferry rope, and the water carried him swiftly downstream.

About a quarter of a mile down the canyon, other workmen must have been horrified when they saw a man's body wash over the power company's weir and keep going.

Word of the tragedy reached Provo via the telephone located at the power plant, and the county sheriff organized search parties.

At about one o'clock the next afternoon, John Holman found the body about three miles from the scene of the accident.

It had lodged in some rocks and brush near the bridge at the mouth of the canyon.

Madsen's body bore the marks of its violent ride down the rocky, snag-filled river.

His shoes and socks were the only clothing that remained on the body.

The corpse was covered by cuts and bruises.

Deputy Sheriff Henry took the battered remains to Berg's undertaking parlor.

When folks in the small Sevier County town of Monroe (near Elsinore) heard of Madsen's death, they collected donations to pay the expense of transporting the body home and burying it.

The men of Dennis Palfreyman's grading camp contributed an additional US$16.25 toward the expenses.

Palfreyman added to this sum the US$3.75 the company owed the deceased grader and presented the US$20 to Sheriff Henry.

Arthur Forebush arrived in Provo on 14 Jun 1899 to take the body home.

Next morning he supervised the railroad workers who loaded the body on the train.

It is appropriate that Madsen's long trip home was made possible by a railroad grade.

Canyon Camping

Despite this spate of accidents in the canyon and the death of Madsen, all was not gloom and doom.

Many of the workmen brought their families with them, and the grading camps resembled little villages.

For many family members, the experience resembled an extended outing, although some of the wives helped with the cooking in camp.

Zella Teenie Vincent (Chase) remembered that when she was about 10-years-old, her family camped in the canyon while her father was working.

Her mother cooked for the men who were laying track for the Rio Grande Western.

To while her time away, young Zella crawled up near a deep hole in the creek running down South Fork and watched the big trout.

Some of the fish weighed up to six pounds.

She later reminisced, "I would watch them until I got tired and then drop some pebbles in the water to see them scamper."

Zella wrote that some of the big trout were taken illegally with gigs or spears.

One day a workman came to borrow the camp gig to "get a fish for dinner."

He soon ran back to the Vincent family tent with a large trout, hurriedly threw it inside and said, "Here Teen, hide this quick, the game warden is after me."

Her mother threw the fish under some quilts, and hearing nothing more that day from the fisherman or the game warden, cooked the trout, and the family ate it for supper.

Signs hanging from some of the family tents advertised summer refreshments, and in other tents women carried on a regular restaurant business.

One of the Provo papers reported that signs on the cook tents carried advertisements such as "Fish Dinner, only 25 cents."

Despite the accidents, road grading and track laying progressed at a reasonable pace, and the track crews finished the railroad to Nunns Power Plant early in June.

Now they were ready for the final stretch to Heber.

D. Robert Carter.

(likely no image with original article)

(usually because it's been seen before)

(the image is altered or fake)

provisions in Section 29 of the

Canadian Copyright Modernization Act.