Archive

Preface

Introduction

Construction

Superintendent

Service

Eastwards

Quebec

Tunnel

Maritimes

Expansion

Ontario

Mountains

Superior

M.H. McLeod

Mackenzie & Mann

Credits

News

Links

Background

"Being an extract from a manuscript entitled "Canadian Railway Development from the Earliest Times" by Norman Thompson and Major J.H. Edgar, B.Sc., A.M.E.I.C."

Unlike the Canadian Pacific, the second transcontinental railway evolved from a series of detached fragments, silently and obscurely joined together until the time became ripe for the real objective to be announced. The building of the Canadian Northern Railway forms, indeed, the most distinctive exhibition of Canadian expansion during the Twentieth Century. From the initial section on the western prairie there grew up steadily a system that ultimately stretched from Quebec and Ontario to the Pacific, with even a detached output by the Atlantic. The achievement of Mackenzie and Mann may well be said to supply not inconsiderable part of the romance connected with Canadian railway transportation. The singular strategic skill displayed enabling the small beginnings to become developed into a transcontinental competitor before the full significance of what was transpiring could be thoroughly appreciated. A policy was pursued of acquiring by degrees, isolated charters, whose import appeared only after incorporation into the general system. Somewhere there exists a diagram showing these charters, and it is said to present an aspect resembling an elaborate genealogical tree of the English Kings, including the Heptarchy.

may well be said to supply not inconsiderable part of the romance connected with Canadian railway transportation. The singular strategic skill displayed enabling the small beginnings to become developed into a transcontinental competitor before the full significance of what was transpiring could be thoroughly appreciated. A policy was pursued of acquiring by degrees, isolated charters, whose import appeared only after incorporation into the general system. Somewhere there exists a diagram showing these charters, and it is said to present an aspect resembling an elaborate genealogical tree of the English Kings, including the Heptarchy.

During 1889 the Lake Manitoba Railway & Canal Company obtained power to build via Northwestern Manitoba to tidewater on Hudson Bay through territory originally selected for a Canadian Pacific line, the Provincial Government displaying a favorable attitude notwithstanding which the scheme failed to prosper. In 1896 this charter was acquired by William Mackenzie and Donald Mann (who had formed a partnership in 1888). 85 miles were constructed the same year and the first commercial train ran on 15 Dec 1896 from Gladstone in Dauphin, hauled by one of the two engines available. This formed the initial link in what was destined to develop into the Canadian Northern System, rather than an East and West line. Bearing in mind the interest since taken in the Hudson Bay Railway this fact is of particular significance, the Mackenzie-Mann plans having become diverted from the aspiration to reach Hudson Bay by inducements to strike West instead. Construction had progressed as far as Sifton by the end of 1896, and Winnipegosis was reached during the following year, this place being situated on the lake of the same name 124 miles from Gladstone, and now forming the terminus of a short branch.

by the end of 1896, and Winnipegosis was reached during the following year, this place being situated on the lake of the same name 124 miles from Gladstone, and now forming the terminus of a short branch.

The duties of a Superintendent on a pioneer railway of this description were both varied and exacting as exemplified by the following incident: One bitterly cold night in February the train was en route from Dauphin to Gladstone and Portage la Prairie when, as Glenella was approached, the engine coughed herself into impotence, due to leaky tubes arising from a plethora of cold air, and with difficulty managed to haul her load into the siding. The temperature registered 30 degrees below zero, and the witching hour of midnight was recorded on one's watch. In close proximity there dwelt a recently arrived settler who was roused for the purpose of driving to Plumas 13 1/2 miles, whence it would be possible to despatch a telegram ordering a fresh engine.

Sitting in the bottom of a wagon-box set upon a home made jumper sleigh, the Superintendent and settler drove off over the trail less expanse of snow with never a star to guide, the driver exhibiting signs of being almost as inert as the engine, but asserting, nevertheless, that he was acquainted with the way across the flat, hoary plain. After 3/4 of an hour had elapsed this individual admitted himself to be at fault, and horses, left to themselves, brought the sleigh in half an hour to within sight of the gleaming red light shown by the helpless train. Bidding the farmer good morning, at 01:30, the Superintendent grasped a kerosene lamp and started tramping the sleepers to Plumas. Before a mile had been covered the lamp ceased to function, and on reaching the bridge over Jumping Deer River, the timbers were found coated with ice. It quickly became demonstrated that the food cannot say to the hand, "I have no need of thee", but at length the troublesome trestle was safely negotiated, and hope of gaining Plumas flickered up once more in a lonely human breast. The station being attained at 05:30, the Agent's slumbers were rudely disturbed, and assistance sought from Portage la Prairie, whence a Manitoba & North Western locomotive steamed to succour the derelict at Glenella, and then the Superintendent went to bed.

The first timetable of the Lake Manitoba Railway & Canal Company saw the light on 3 Jan 1897, when one mixed train was operated in each direction once a week, running rights being enjoyed between Portage la Prairie and Gladstone over the Manitoba & North Western. "Service" formed the motto in those days, more stopping places being provided to the mile, in all probability, than on any other railway in the world, for along most of the route, settlement had only just commenced, passengers and way freight being handled to suit the pleasure of patrons. 6 1/2 hours were occupied by the mixed train running from Portage la Prairie to Dauphin

of the Lake Manitoba Railway & Canal Company saw the light on 3 Jan 1897, when one mixed train was operated in each direction once a week, running rights being enjoyed between Portage la Prairie and Gladstone over the Manitoba & North Western. "Service" formed the motto in those days, more stopping places being provided to the mile, in all probability, than on any other railway in the world, for along most of the route, settlement had only just commenced, passengers and way freight being handled to suit the pleasure of patrons. 6 1/2 hours were occupied by the mixed train running from Portage la Prairie to Dauphin , the latter place deriving its name from a neighbouring lake, which had been so christened by an early French explorer. On the two nights of the week when the train was due there, a large crowd would be waiting at the station to extend a welcome, sometimes conveying to immigrants a false impression of the importance attached to their arrival by the inhabitants. The Superintendent almost lived on the line, and frequently lent his aid in handling traffic, this being fundamentally a colonization railway.

, the latter place deriving its name from a neighbouring lake, which had been so christened by an early French explorer. On the two nights of the week when the train was due there, a large crowd would be waiting at the station to extend a welcome, sometimes conveying to immigrants a false impression of the importance attached to their arrival by the inhabitants. The Superintendent almost lived on the line, and frequently lent his aid in handling traffic, this being fundamentally a colonization railway.

Before long Mackenzie-Mann interests sought another field in which to exercise their activities, and during 1898 they commenced construction of a line from Winnipeg for conveying wheat to Lake Superior for shipment, this being known as the Manitoba & South Eastern. Four hundred miles East of the growing prairie centre there already existed a stretch of track extending from Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) towards Duluth, Minnesota, owned by the Port Arthur Duluth & Western Railway . This was purchased and a start made in linking it with the Manitoba & South Eastern, such connection being required in accordance with the charter of the Ontario & Rainy River Railway near Rainy Lake

. This was purchased and a start made in linking it with the Manitoba & South Eastern, such connection being required in accordance with the charter of the Ontario & Rainy River Railway near Rainy Lake . Whilst these initial steps were being taken in apparently haphazard fashion, property for terminal purposes was secured in Winnipeg, and plans were prepared for an advance through the Saskatchewan Valley to Edmonton, Alberta.

. Whilst these initial steps were being taken in apparently haphazard fashion, property for terminal purposes was secured in Winnipeg, and plans were prepared for an advance through the Saskatchewan Valley to Edmonton, Alberta.

During the winter of 1898 the first section of the Manitoba & South Eastern Railway was opened from St. Boniface to Marchland, about 45 miles distant, a typewritten timetable being considered adequate for announcing the initial service. Commodities carried in early days consisted largely of cordwood from the swamps destined to keep Winnipeg warm, and 90 percent of the traffic comprised train loads of Tamarack, Poplar, and Jackpine. A commencement was made with two engines, fifty new freight cars, two second hand passenger cars, and an uncertain number of flat cars for the cordwood, such as could be collected from the Canadian Pacific yard without asking permission. Sir William Whyte looking down from his office window on this proceeding used to frequently laugh over it, nevertheless the "Muskeg Limited" as the train became known, occupied its own peculiar place in Winnipeg transportation, and the nickname is worthy of preservation. The title "Canadian Northern Railway" was adopted in 1901, and during the same year the Company received a valuable addition to its sphere of operation by acquisition of the Northern Pacific lines in Manitoba, previously taken over by the Provincial Government for re-disposal, the early history of which presents some remarkable incidents, which however is quite another story. This step gave the Canadian Northern the use of Water Street Station in Winnipeg, the connection from St. Boniface being put in service during that year also. Opening of the Union Station in 1911 resulted in the conversion of the older one to other uses, but the iron gates possess historic significance by still displaying the monogram "N.P.& M." (Northern Pacific & Manitoba).

The East was also at this time embarking upon railway enterprises that failed to eventuate in accordance with the anticipations of their promoters, but which have, none the less, played a vital part in the system's subsequent economic development, the most remarkable of these local pioneering efforts being the Quebec & Lake St. John Railway , built for colonization purposes. The early financial troubles of this Company assume a romantic aspect when viewed through the kindly veil of time, but were grievous to be borne at the moment, for instance, occasions arose when the train could not start from the station at Quebec until the General Manager had contrived to borrow sufficient money from the passengers wherewith to purchase coal for the engine.

, built for colonization purposes. The early financial troubles of this Company assume a romantic aspect when viewed through the kindly veil of time, but were grievous to be borne at the moment, for instance, occasions arose when the train could not start from the station at Quebec until the General Manager had contrived to borrow sufficient money from the passengers wherewith to purchase coal for the engine.

The promoters of the Quebec & Lake St. John also commenced construction of the Great Northern Railway of Canada, whose primary object was to connect the city of Quebec with Montreal. Canadian Northern interests later obtained control of both lines, including sidings and other facilities at Quebec Harbour, adopting the title "Canadian Northern Quebec Railway" for the combination. When the Great Northern transfer took place in 1901, that railway possessed a branch from Joliette to St. Catherine Street East station in Montreal, the main line extending from Limoilou Junction in the suburbs of Quebec City, to Hawkesbury

station in Montreal, the main line extending from Limoilou Junction in the suburbs of Quebec City, to Hawkesbury , Ontario, 225 miles involving considerable bridge work in carrying the track over the Ottawa River

, Ontario, 225 miles involving considerable bridge work in carrying the track over the Ottawa River to its South shore. After changing hands, construction continued to Ottawa

to its South shore. After changing hands, construction continued to Ottawa and a temporary wooden station was built on the outskirts, perched at the summit of an uncompromising hill. The old Moreau Street Station in Montreal (otherwise St. Catherine Street East) which is still in use, came into prominence during the war in connection with the en-training of troops for Valcarier Camp

and a temporary wooden station was built on the outskirts, perched at the summit of an uncompromising hill. The old Moreau Street Station in Montreal (otherwise St. Catherine Street East) which is still in use, came into prominence during the war in connection with the en-training of troops for Valcarier Camp , the Canadian Northern route from Ottawa being also used for the same purpose.

, the Canadian Northern route from Ottawa being also used for the same purpose.

In order to avoid the long detour by Joliette for traffic between Ottawa and Montreal, including use of the inconveniently placed existing station in the latter city, and ambitious scheme was devised for penetrating to the business centre of Montreal in connection with a new direct line. The topographical situation of Montreal is such that the avenues of approach for railways are however necessarily few, and those formerly available had long since been fully occupied by competitive companies, hence the drastic expedient was adopted of boring a tunnel more than three miles from end to end through the stubborn limestone of historic Mount Royal, and beneath several busy streets lined with massive buildings. The platforms at the station, which is designated the Tunnel Terminal

more than three miles from end to end through the stubborn limestone of historic Mount Royal, and beneath several busy streets lined with massive buildings. The platforms at the station, which is designated the Tunnel Terminal , lie below street level, but open to the daylight, and are reached by descending from the circulating area opening onto Lagauchetiere Street. The tunnel and station were completed in October 1918, through trains being worked with electric locomotives

, lie below street level, but open to the daylight, and are reached by descending from the circulating area opening onto Lagauchetiere Street. The tunnel and station were completed in October 1918, through trains being worked with electric locomotives from the terminus to Lazard, seven miles away, in addition to which numerous suburban trains are hauled by the same agency to Cartierville conveys at the rear portion for the main line onto which a steam engine backs at Lazard. This notable tunnel was built to accommodate two tracks, and the line continues from the Northern Portal to effect a junction with the former Great Northern Railway at Hawkesbury, which in connection with improvements also made in the vicinity of Ottawa, resulted in providing a short route between the central station in the Capital City and the Tunnel Terminal in the commercial metropolis of Quebec province.

from the terminus to Lazard, seven miles away, in addition to which numerous suburban trains are hauled by the same agency to Cartierville conveys at the rear portion for the main line onto which a steam engine backs at Lazard. This notable tunnel was built to accommodate two tracks, and the line continues from the Northern Portal to effect a junction with the former Great Northern Railway at Hawkesbury, which in connection with improvements also made in the vicinity of Ottawa, resulted in providing a short route between the central station in the Capital City and the Tunnel Terminal in the commercial metropolis of Quebec province.

While the foregoing events were transpiring in Quebec, the Canadian Northern was busily engaged in extending its operations further East. Nova Scotia desired a route which should follow the marvelously indented South Shore from Halifax to Yarmouth, and the Halifax & South Western Railway was therefore built to meet the link between Yarmouth and Barrington previously acquired by the same interests. The Northern portion constituted a development of an earlier undertaking, the Nova Scotia Central, the first sod having been turned at Lunenburg on 10 Aug 1877. This ceremony having evidently been a rather elaborate one was brightened by the presence of the Town Band which played a selection after each of the eight addresses that were delivered, and the thoroughness of the speechmaking seems to have been equalled by that of the cheering. Cheers were given for the Queen, for the President of the United States, for the Ladies of Lunenburg, for those concerned in the enterprise, and for the workmen gathered around. The Nova Scotia Central, opened during 1889, afforded a much needed outlet to a most productive section of country, lumber moving over it in large quantities from the start. The dismal prognostications furnished by opponents, who had long indulged in ridicule, were emphatically discounted by actual results obtained after traffic had commenced. The Halifax & South Western main line was completed throughout in December 1906, and the Caledonia Branch three years earlier. Inverness grew to its present status as a town through the development of coal measures on the west coast of Cape Breton Island, for in order to bring this fuel conveniently to a shipping port, 61 miles of track were built in 1901 to Port Hastings and Point Tupper on the Strait of Canso. New Brunswick also desired to benefit by Canadian Northern activities, and that Province was one of only two (Prince Edward Island being the other) in which the System lacked a foothold within ten years of the founding of Dauphin in a Manitoban wheat field.

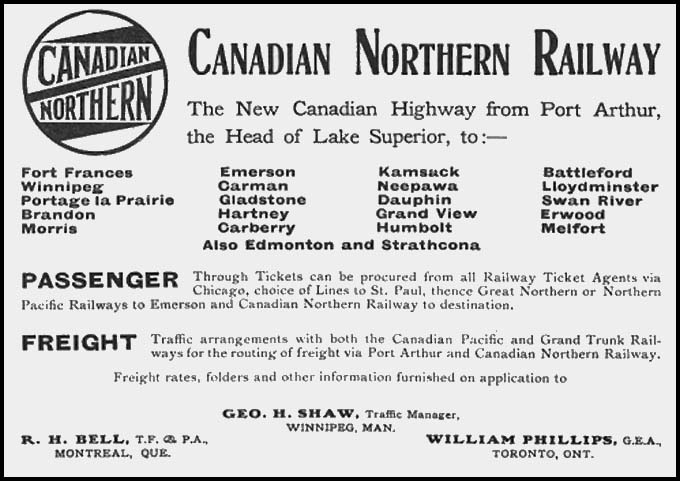

Progress continued in the many projects connected with expansion of the System both east and west, in a marked manner. The charter of the Morden & North Western Railway being added during 1901, and early in the following year, the Canadian Northern link between Port Arthur and Winnipeg being completed and the first through train operated, so that by June the total mileage rose to 1,248.

and Winnipeg being completed and the first through train operated, so that by June the total mileage rose to 1,248.

During 1904 expansion continued by the two methods, 441 miles being constructed, and 252 brought within the sphere of influence. Throughout the ensuing year the utmost vigour was employed in pushing the realization of the Company's plans, the policy being to render each section, as built, self-supporting. On 24 Nov 1904, amid much ceremony and local rejoicing, the railway entered Edmonton , the Capital of the Province of Alberta, and for long an important trading centre, and the completion

, the Capital of the Province of Alberta, and for long an important trading centre, and the completion of lines to Edmonton and Prince Albert

of lines to Edmonton and Prince Albert marked a momentous advance in the forward march of the Canadian Northern System.

marked a momentous advance in the forward march of the Canadian Northern System.

An important link is afforded by the line connecting Regina, Capital of Saskatchewan, with Saskatoon , another hub of railway activity, and Prince Albert, as the greater portion forms an additional route for through traffic between Winnipeg and Edmonton. Prince Albert is the largest city in the Prairie Provinces north of Edmonton, and forms the northern limit of railway travel in that part of Canada. The railway under notice, formerly known by the cumbersome title of the "Qu'Appell Long Lake & Saskatchewan", was originally owned by English capitalists, being operated and equipped by the Canadian Pacific under a lease, on the termination of which it came into the Canadian Northern fold. This is the most notable case of a railway being transferred from one competitor to another.

, another hub of railway activity, and Prince Albert, as the greater portion forms an additional route for through traffic between Winnipeg and Edmonton. Prince Albert is the largest city in the Prairie Provinces north of Edmonton, and forms the northern limit of railway travel in that part of Canada. The railway under notice, formerly known by the cumbersome title of the "Qu'Appell Long Lake & Saskatchewan", was originally owned by English capitalists, being operated and equipped by the Canadian Pacific under a lease, on the termination of which it came into the Canadian Northern fold. This is the most notable case of a railway being transferred from one competitor to another.

While these events were transpiring in the West, construction was proceeding in Ontario, and the formal opening of the trunk line from Toronto to Parry Sound, and important point on Georgian Bay en-route to Sudbury and Port Arthur, took place in 1906, this line being destined to eventually connect Toronto with Winnipeg and Vancouver. On 3 Jul 1908, traffic was inaugurated between Toronto and Sudbury , the latter being an important mining centre in Northern Ontario.

, the latter being an important mining centre in Northern Ontario.

The previous year, however, witnessed a severe diminution in the rate of progress recorded, due to unprecedented weather conditions, and their effects. The winter of 1906-1907 is regarded as having proved the most rigorous of any experienced during a long period in the history of the Prairie Provinces, a train being reported as leaving Winnipeg on 28 Mar 1907, and failing to arrive at Edmonton until 14 Apr 1907. Under such circumstances numerous complaints accrued, and conditions were unfavourable to the building of extensions, which policy was therefore temporarily discontinued.

Construction from Saskatoon towards Calgary however, started in 1907, and by the end of 1909, track had been laid to Kindersley, Saskatchewan, a distance of 125 miles, and by 1912 to Hanna, Alberta, an additional 137 miles. During this interval the district filled up with great rapidity, and the newly laid line became taxed to capacity in order to cope with the carriage of settlers' effects, merchandise, coal, and in hauling out the grain. Connection followed to Drumheller in 1913, and thereafter to Calgary, which was reached in 1913. The Red Deer River proved a formidable obstacle to negotiate, but the coal working at that point commenced by the pioneer "Sam Drumheller" at once attained prominence, and eventually the number of producing mines amounted to 28 scattered about the region.

In 1918 it was decided to build 20 miles of second track between Munson Junction, where the lines from Saskatoon and Edmonton to Calgary converge, and Wayne, to relay the whole line with 85 pound steel rails, to replace the wooden trestles with concrete structures and solid embankments, to extend sidings, and to provide additional passing tracks, arrangements being also made to reduce the number of river crossings by diverting either the railway or the river in the Rosebud Valley. The original route entailed the erection of no less than 67 woodpile bridges, and it was planned to abolish many of these, leaving but 29 permanent crossings executed in steel and concrete, in their place.

Reverting to the mountains, the railway builder found a worthy foe when he essayed to level a path for his rails in British Columbia, bridge across mountain streams or rocky gorges, tunnel through shoulders of rock, benches cut out of solid rock, embankments long and heavy, were the rule and not the exception. The civil engineer had his hands full, and was provided with a succession of problems to his heart's content.

Almost any mile of the construction would form a gripping story in itself, and the ingenuity of both engineer and contractor was continually pressed to the limit.

It was said that certain parts of the line between Kamloops and the Fraser River that did not slip into the water in the spring would get there in the fall. For miles, access to the work along the Fraser Canyon was effected by means of steel cables slung across the river, from which were suspended buckets or slings traveling beneath them, and in these, all the men and material employed were transported. In the initial stages of mountain building, engineering parties might have been observed crawling on the faces of the cliffs, prevented from falling by ropes hung from above. Having determined the location of the roadbed, the next step consisted in notching out a foot trail so to provide the first means for directing a real attack on the rock to be moved.

The actual blasting in large or small quantities is a matter of only a second or two at most, aside from the removal of the broken fragments, the labourious portion of the operation consist in driving the holes into which are to be rammed the explosive charges. These may be only small drill holes, a few feet in depth, and a little more than an inch in diameter, or a set of burrows forming in reality a small tunnel with a series of pockets which will be loaded with the necessary charges of dynamite or black powder, or both, to lift or break out the rock at the point of least resistance. Often tens of thousands of cubic yards are moved or disintegrated by one shot, numbering several tons of explosives.

Ordinarily to achieve a foot or two a day on each end of a rock tunnel was regarded as constituting good progress. En-route to Vancouver there exist 39 tunnels, all but four having been pierced through solid rock varying from less than 200 feet to over half a mile in length. Mountain streams come into flood with melting snows and reach raging proportions if rains should be co-incident, so that to successfully place the footings for a bridge in these rivers is a matter of choosing the appropriate season. Frequently a whim of nature catches part of the work unfinished, however, and wipes it out. The inference should not be drawn from the foregoing remarks that the mountain work on the Canadian Northern was confined solely to British Columbia, as the boundary between that Province and Alberta runs along the summit of the Rockies, and many engineering difficulties were encountered in climbing from the prairies through the foothills to the Continental Divide. The last spike was driven at Basque

there exist 39 tunnels, all but four having been pierced through solid rock varying from less than 200 feet to over half a mile in length. Mountain streams come into flood with melting snows and reach raging proportions if rains should be co-incident, so that to successfully place the footings for a bridge in these rivers is a matter of choosing the appropriate season. Frequently a whim of nature catches part of the work unfinished, however, and wipes it out. The inference should not be drawn from the foregoing remarks that the mountain work on the Canadian Northern was confined solely to British Columbia, as the boundary between that Province and Alberta runs along the summit of the Rockies, and many engineering difficulties were encountered in climbing from the prairies through the foothills to the Continental Divide. The last spike was driven at Basque , B.C., in 1915, but as the Great War was then raging this noteworthy event secured little public notice.

, B.C., in 1915, but as the Great War was then raging this noteworthy event secured little public notice.

The section from Fort William (now Thunder Bay) to Winnipeg became finally linked on 1 Jan 1902, when the last spike was driven by Mackenzie and Mann in the shadow of a splendid white pine near Fort Frances , the spot being called Hanna's Point, in recognition of the General Manager, who was a passenger on the first through train. Port Arthur having been left at 10:00 on 31 Dec 1901, on arrival at Fort Frances it was found that eighteen feet of rail still remained unlaid. After this hiatus had been dealt with, and the ceremony performed, the train proceeded, reaching Winnipeg 36 hours after leaving Port Arthur. It consisted of three cars, one named "Sea Falls", a parlour car, and the car "Keewatin" supplied for the occasion by the Canadian Pacific Railway. On 30 Jun 1908, the mileage owned, leased, or operated by the Company totalled no less than 2,894, and at the close of the year this figure had risen to 3,100, or including lines located in Eastern Canada, the respectable sum of 5,400 miles. The year 1909 witnessed continued expansion, 482 miles located in five different provinces being added, besides 398 miles levelled in readiness for tracklaying. During the first 18 years an average of nine furlongs per day was achieved (1 furlong = 220 yards about 201 metres).

, the spot being called Hanna's Point, in recognition of the General Manager, who was a passenger on the first through train. Port Arthur having been left at 10:00 on 31 Dec 1901, on arrival at Fort Frances it was found that eighteen feet of rail still remained unlaid. After this hiatus had been dealt with, and the ceremony performed, the train proceeded, reaching Winnipeg 36 hours after leaving Port Arthur. It consisted of three cars, one named "Sea Falls", a parlour car, and the car "Keewatin" supplied for the occasion by the Canadian Pacific Railway. On 30 Jun 1908, the mileage owned, leased, or operated by the Company totalled no less than 2,894, and at the close of the year this figure had risen to 3,100, or including lines located in Eastern Canada, the respectable sum of 5,400 miles. The year 1909 witnessed continued expansion, 482 miles located in five different provinces being added, besides 398 miles levelled in readiness for tracklaying. During the first 18 years an average of nine furlongs per day was achieved (1 furlong = 220 yards about 201 metres).

In less than 20 years the Canadian Northern developed from a small pioneer railway operated by a staff numbering 14, including all departments, into a system which served centres of 1,000 population and over, representing 97 percent of the inhabitants in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and 90 percent of those in Alberta. Between 600 and 700 towns and shipping points came onto the map directly through this Company's activities.

During the spring of 1883 the first steamer load of passengers bound for Winnipeg from an Ontario port arrived at Port Arthur. Among them was a young engineer named McLeod, who had served as chairman on the Credit Valley line in Ontario, and was on his way to the Lake Superior district of the Canadian Pacific. He filled a wonderful destiny in becoming Chief Engineer and General Manager of the Canadian Northern, and in building more railway in the prairie country than any other man.

Some day perchance, fitting tribute will be paid the railway engineers who have wrought so magnificently in transforming the face of Canada. M.H. McLeod commenced duty as Chief Engineer of the Canadian Northern in the spring of 1900, at which time the mileage was but 600. The quality of the railway pathfinder is essentially the same whether he walks alone in the depth of winter on Saskatchewan ice, looking for a place to build a steel bridge a thousand feet long, or whether he is wandering round Toronto's wharves littered with shipping warehouses, planning improved approaches to a new station. He is in a class of his own, but also belongs to a great company of engineers to whom ungrudging admiration is richly due, and too seldom accorded. McLeod was a born, incurable, unconquerable, pathfinder. He would set out to discover country well adapted for settlement and for a settlers' railway, and not only find what he wanted, but at the same time, would devise some improvement in the location determined upon by his staff for other lines, that saved thousands of dollars in construction. Those serving under the Chief also exhibited similar qualities, and in this connection an amusing episode is related by one of the Profession. While in charge of some surveys on the prairie and explorations involved thereby, he was called upon to spend the working hours of three or four months on horseback. Upon one occasion a friend offered to sell him a horse and he enquired, "Does he buck?" "Well," replied the owner, "this horse has never bucked with me." The engineer purchased the animal and during the first day in the saddle was thrown violently from his mount. Meeting the vendor a few days later he remarked, "I thought you stated that this horse would not buck?" "No", answered the other, "I did not say that. I said that the horse had never bucked with me, which is perfectly true, as I was never on his back."

commenced duty as Chief Engineer of the Canadian Northern in the spring of 1900, at which time the mileage was but 600. The quality of the railway pathfinder is essentially the same whether he walks alone in the depth of winter on Saskatchewan ice, looking for a place to build a steel bridge a thousand feet long, or whether he is wandering round Toronto's wharves littered with shipping warehouses, planning improved approaches to a new station. He is in a class of his own, but also belongs to a great company of engineers to whom ungrudging admiration is richly due, and too seldom accorded. McLeod was a born, incurable, unconquerable, pathfinder. He would set out to discover country well adapted for settlement and for a settlers' railway, and not only find what he wanted, but at the same time, would devise some improvement in the location determined upon by his staff for other lines, that saved thousands of dollars in construction. Those serving under the Chief also exhibited similar qualities, and in this connection an amusing episode is related by one of the Profession. While in charge of some surveys on the prairie and explorations involved thereby, he was called upon to spend the working hours of three or four months on horseback. Upon one occasion a friend offered to sell him a horse and he enquired, "Does he buck?" "Well," replied the owner, "this horse has never bucked with me." The engineer purchased the animal and during the first day in the saddle was thrown violently from his mount. Meeting the vendor a few days later he remarked, "I thought you stated that this horse would not buck?" "No", answered the other, "I did not say that. I said that the horse had never bucked with me, which is perfectly true, as I was never on his back."

Nothing in North American transportation history quite parallels the career of the Canadian Northern during its 26 years of independent operation. Mackenzie and Mann were indeed unique among the railway builders of the Continent. They performed a feat which no United states combination ever achieved. Their enterprise was more original than anything carried through by James Hill. Their pioneer railway induced settlement a hundred miles north of the line beyond which implement manufacturers had refrained from extending credit. They went where railway obligation was afraid to venture, they possessed the pioneering, constructive, passion which made of them Great Canadians. They were so saturated with this spirit that it was more difficult to keep them from getting in advance of traffic than to fulfill the promises given. The whole project was marked by the simplicity shown by all works of genius, although the most bewildering and intricate corporate financing that Canada had ever known took place. The planning was constructive, the strategy admirable in the selection of routes during the early years, and the service rendered the prairie country invaluable. William Mackenzie, Master planner and financial wizard, Donald Mann with his forcefulness, and Zebulon Lash, subtlest framer of legal clauses and monetary expedients in the annals of Canada formed indeed a trio worthy of each other and of the mighty task in hand.

The adventurous career of the Canadian Northern Railway System as a separate entity was brought to a close in 1918, when it passed under control of the Dominion Government. On 12 Jul 1920, an Order-in-Council was published appointing the Board of Directors who were administering the former Canadian Northern Railway to be managers of the Grand Trunk Pacific also, immediately afterwards the official staffs of the two lines became amalgamated and reorganized, the departmental officers and their employees being included in the consolidation.

Norman Thompson and Major J.H. Edgar - The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin No. 28 (May, 1932), pages 55-63, published by the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society (R&LHS).

28 Jan 2015 - The Last Spike for the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway

10 Dec 2021 - Events in Manitoba and Alberta to Mark 125th Anniversary of Canadian Northern Predecessor

16 Dec 2021 - Canadian Northern Railway Celebrates 125 Years

Canadian Northern Railway Wikipedia

Canadian Northern Pacific Railway Wikipedia

Canadian Northern Railway Society

Port Arthur, Duluth & Western Railway (1)

Port Arthur, Duluth & Western Railway (2) (Link fails 5 Dec 2022)

The Canadian Northern Railway station at Winnipegosis with Canadian Pacific passenger cars present - 1897 Photographer? - Library and Archives Canada.