Great Western Railway

London England

United Kingdom

N51.515566 W0.175682

(Paddington Station)

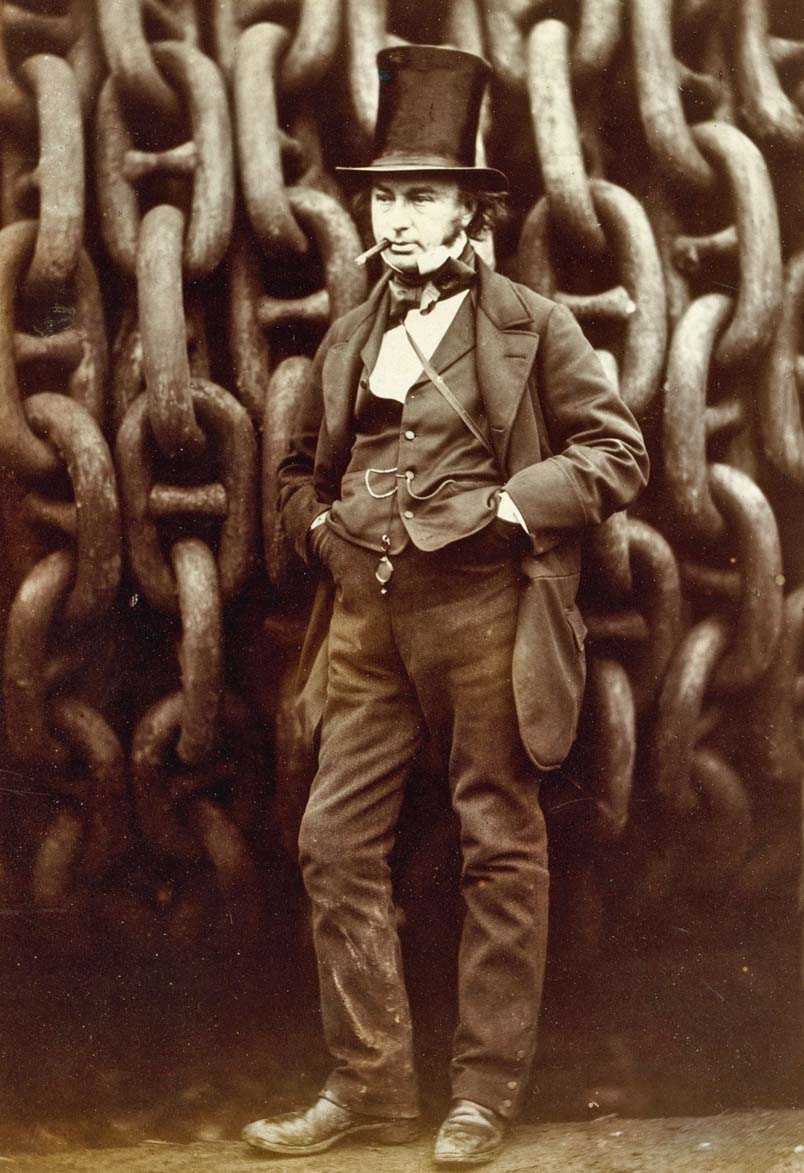

(Paddington Station)To appreciate today's Great Western Railway (GWR) we need to recognize this important fellow shown on the right. His rather unusual name is Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and were it not for his efforts, there would likely be no GWR today. He was named Isambard after his French Civil Engineer father while Kingdom was his English mother's name. Brunel was born on 9 Apr 1806 in Portsmouth. His father can be attributed as the person starting his son along his history making path. By the age of four he was drawing and had learned Euclidean geometry by age eight. At fourteen he was enrolled in the University of Caen in Normandy, then at Lycee Henri-IV at Paris. Refused entry to the prodigious engineering school Ecole Polytechnique Brunel assumed an apprenticeship under master clockmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet until 1822 when he returned to England.

Along with his father who was chief engineer, Brunel participated as assistant engineer, in the creation of the Thames River Tunnel in London. A tunneling shield designed by his father was used to protect workers during construction through water logged sediment and loose gravel, nevertheless, in 1828, flooding still occurred killing several workers and injuring Brunel who never returned to the project. The tunnel finally opened to the public in 1843. In 1865 the tunnel was purchased by the East London Railway Company and by 1869 trains were using it. It eventually became part of the London Underground system.

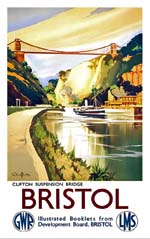

Many bridges were designed by Brunel including the famous Clifton Suspension Bridge at Bristol. 702 feet long and 249 feet above the River Avon it was the longest in the world when completed in 1864, five years after Brunel's death at the age of 53. Another example of his work is the Maidenhead railway Bridge over the Thames River in Berkshire. It is the flattest, widest, brick arch bridge in the world and is still carrying main line trains even though today's trains are about ten times heavier than in Brunel's time.

Building designs include Paddington Station London, opened in 1854, Temple Meads Station in Bristol, and smaller stations such as Culham, Mortimer, Charlbury, and Bridgend.

There are two other Brunel design concepts that immediately come to mind, the Atmospheric Railway, and the SS Great Britain. While his Atmospheric Railway was partially successful it failed due to a leather seal. It was a simple idea in that a tube was laid between railway rails with a slot running along its' length. A piston attached to a carriage riding on the rails was pushed along this tube by atmospheric air pressure while pumping stations along the route provided the vacuum. The problem was with the leather seal along the slot. Without modern lubrication available animal tallow was used as the grease, which supposedly attracted the rats, who ate the seal, thereby rendering the system too leaky to function properly. That's the legend that's evolved over the years but it isn't true, the leather seal failed due to freezing causing it to be too stiff or because of too much heat causing it to dry out and leak.

Brunel, having accomplished the above and more, also came up with the idea for the broad gauge railway, 7 feet and 1/4 inch in width. In 1833 he was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway. It was his vision a passenger would be able to purchase a ticket in Paddington Station, London, and travel from there to New York, changing to a steamship. Perhaps this was his incentive for designing the SS Great Britain? Brunel surveyed the entire route from London to Bristol. It was at this time he made the decision to built a broad gauge railway because he believed it would offer superior running at high speeds although controversial at the time because most other lines were standard gauge. Following Brunel's death it was decided that standard gauge would be used for all British railways.The GWR comprised a number of outstanding features such as large viaducts, specially designed stations, and the Box Tunnel, the longest in the world at that time. While the early broad gauge locomotives built to Brunel's specifications were unsatisfactory, improvements were made at the railway's locomotive works, soon constructed at Swindon. The achievements of the Great Western Railway are now immortalized at the Steam Museum of the Great Western Railway at Swindon. The Didcot Railway Centre has reconstructed a segment of broad gauge track, as well as having a replica of the very rare broad gauge locomotive Iron Duke which was constructed in 1985.

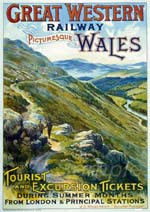

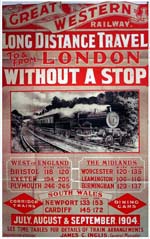

Today the Great WESTERN Railway is an entirely appropriate name as the line covers many communities in a large geographical area west of London and as far west as Penzance on the southwest tip of England in Cornwall. More than 150 years after its creation, the original mainline is described as a masterpiece of railway design. Lying westwards from Paddington, the line crosses River Brent valley on Wharncliffe Viaduct then the River Thames on Maidenhead Bridge, at the time it was the largest span of a brick arch bridge ever built. The line then continues through Sonning Cutting before reaching Reading after which it crosses the Thames twice more. Between Chippenham and Bath is Box Tunnel, the longest railway tunnel at the time. Several years later, the railway opened the longer Severn Tunnel to carry a new line between England and Wales beneath the Severn River to reach Cardiff and Swansea.

| Class 43 | InterCity 125 |

| Class 57 | Tintagel Castle |

| Class 150/1 | Sprinter |

| Class 150/2 | Sprinter |

| Class 158 | Express Sprinter |

| Class 165 | Turbo |

| Class 166 | Turbo Express |

| Class 387 | Electrostar |

| Class 769 | Flex |

| Class 800 | Intercity Express Train |

| Class 802 | Intercity Express Train |