Cajon Pass (pronounced, "KA-HOAN," which means box in Spanish) is indeed, a box canyon, located just northwest of San Bernardino, California, and less than 65 miles from downtown Los Angeles. It is the result of the San Andreas Fault, which splits two mountain ranges, the San Bernardino and San Gabriel. In 1885 the California Southern Railroad opened the first usable and efficient transportation corridor through the region, which later became the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe's (ATSF) main line. The project was spearheaded during the 1880s under ATSF's most influential and important leader, William Barstow Strong. He outmanoeuvred Southern Pacific's Collis P. Huntington for access into the Golden State and eventually established service to all of its major cities.

In 1851, a group of Mormon settlers travelled through the Cajon Pass in covered wagons on their way from Salt Lake City to southern California. A prominent rock formation in the pass, where the Mormon trail and the railway merge, near Sullivan's Curve, is known as Mormon Rocks.

Following its completion, Cajon Pass provided the Santa Fe with a through corridor to Los Angeles and San Diego, cities which would transform into major ports and commercial centres a century later. Today, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad (BNSF) continues to utilize the pass, as does the Union Pacific Railroad (UP). For many years UP leased the Santa Fe line until predecessor Southern Pacific (SP), acquired by UP in 1996, completed the nearby Palmdale Cut-off in the 1960s.

The UP operates and owns one track through the pass, on the previous SP Palmdale cut-off, opened in 1967. The BNSF Railway had two tracks and began to operate the third main track in the summer of 2008. The railroads shared track rights through the pass, ever since the UP gained track rights on the ATSF portion negotiated under the original Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad.

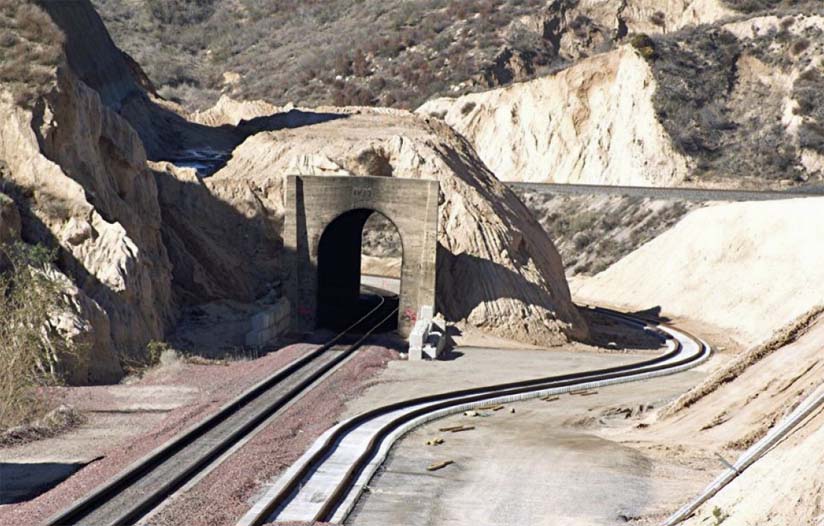

The 3.0 percent gradient for a few miles on the south track is challenging for long trains, making the westbound descent potentially dangerous, as a runaway can, and has, occurred on several occasions. The second track, built in 1913, is 2 miles (3.2 km) longer in order to maintain a lower 2.2 percent gradient. At one time the route contained two tunnels (roughly 500 feet in length), since "daylighted", (removed), as part of improvements undertaken over the years to reduce curves and grades. Railroad improvements in 1972 reduced its maximum elevation from about 3,829 to 3,777 feet, while also reducing the curvature. Trains today travel at speeds of 60 and 70 mph on the straighter track away from the pass, but typically ascend at 14 to 22 mph and descend at 20 to 30 mph.

Class 1 Railroad BNSF, spent US$90 million to build 16 miles of triple track on a portion of the Los Angeles to Chicago "Transcon" intermodal route. During the project, more than 300 BNSF employees and contractors worked on the triple-track project. Crews moved more than 1 million tons of earth, installed about 42,000 concrete sleepers, and laid more than 30 miles of rail. The new third track enables a capacity of 150 trains per day on the BNSF lines. Each intermodal train on these tracks can take more than 250 long-haul road trucks off the region's local highways. Additionally, freight trains are more fuel efficient than trucks and can move one ton of freight more than 400 miles on one gallon of diesel fuel.

Throughout the development process, BNSF worked closely with at least 17 public agencies and six utility companies, as well as the community on issues ranging from enhancement and protection of the environment, to improved grade crossings, drainage structures, as well as preservation of historical and cultural resources.

The triple-tracking will expand BNSF's capacity to meet the growing demand for goods movement and will make this entire segment of the Transcon run smoother. Line speeds will also be improved, and efficiencies gained both for transportation and maintenance activities. Such sustained traffic volumes didn't provide an adequate cushion to allow recovery from unanticipated events. They also placed a strain on maintenance resources attempting to get time to work on the track, sometimes resulting in trains having to stop.

The route up and over the San Bernardino Mountains has two tunnels, Number 1 (about 400 feet long) and Number 2 (about 500 feet long) near Alray just east of the I-15 Freeway. Tunnel Number 2 was eliminated, with the earth over it removed first and then its concrete linings broken up and hauled away. A temporary by-pass track was installed around Tunnel Number 1 so as not to impede daily train operations while it was dismantled. The second track was then constructed on a parallel alignment with the original track through a large cut where the tunnels have stood since 1913. The removal of the tunnels allow for more efficient track maintenance as well as providing improved access to support train operations. Nine high speed crossovers allowing trains to switch from one track to another without slowing down track speed were installed strategically at Summit, Silverwood, Alray, Cajon, and Keenbrook.

A new signalling control system was installed along with some bridges, while others were modified to take the increased loads and stresses. Wherever possible, technology upgrades were installed. Complete track renewals with concrete sleepers and 141lb FB CWR (Continuous Welded Rail) were undertaken everywhere except on bridges and under turnouts. "This project moved about 1 million cubic yards of spoil."

Again this was a significant permanent way project that attracted little worldwide attention, but nevertheless was delivered in harsh conditions by dedicated engineers in some of the USA's most challenging railway environments.

Phil Kirkland.

provisions in Section 29 of the Canadian

Copyright Modernization Act.